Building Falda’s Chiesa Nuova Block

by Abbey Hafer

The city block containing the church of Santa Maria in Vallicella, known as Chiesa Nuova, and the neighboring Oratory and Casa dei Filippini was located in a prominent position in the topography of early modern Rome. The block bordered the Via Papale, a main ceremonial route through the city that was used for each new pope’s possesso procession from St. Peter’s to the Lateran. The church, Oratory, and Casa structures were depicted by Giovanni Battista Falda in several of his etchings, listed below. These architectural structures resulted from almost a century of construction, beginning in 1575 and continuing into the 1660s. Construction of the Chiesa Nuova was initiated following Pope Gregory XIII’s recognition of the Congregation of the Oratory in July of 1575, when he assigned the group, led by future saint Filippo Neri, to a small, dilapidated church called S. Maria in Vallicella. The Oratorians reconstructed the church and expanded the site, acquiring land to the west of the church on which to build a residence for the Congregation.[1] Several architects were involved in the planning and building of the Oratorian complex, most notably Francesco Borromini, the architect responsible for the unorthodox curving brick façade of the Oratory.

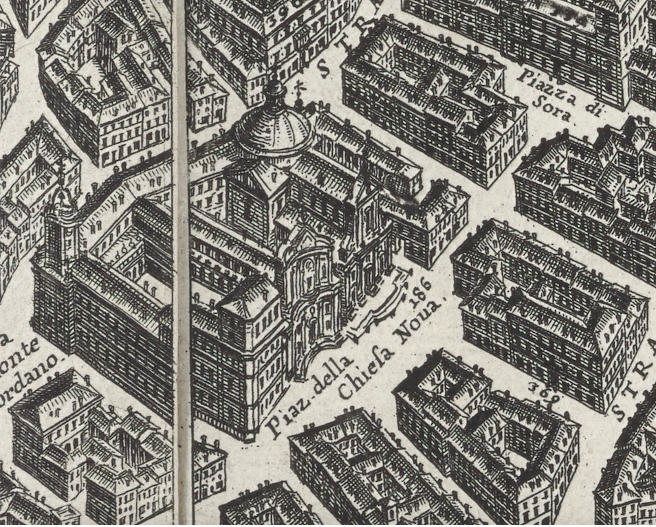

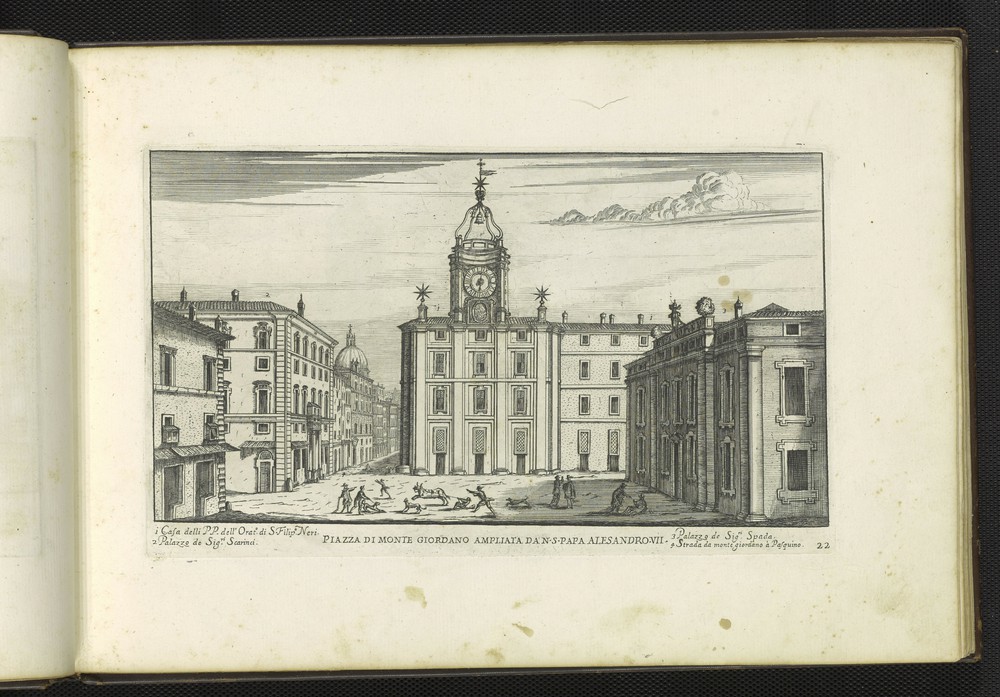

The complete residence, Oratory, and church, with their recognizable paired facades, can be seen in Falda’s 1676 etched map of Rome (Figure 1). He also created three vedute, or city views, of the block published in Il nuovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna in 1665, vol. 1, plates 21, 22, and 23 (Figures 2, 3, and 4). Piazza chiesa é oratorio di Santa Maria in Vallicella detta la Chiesa Nova depicts the two neighboring facades and several more humble buildings to the right of the church from a vantage point across a vast piazza (Figure 2). Two other vedute, Piazza di Monte Giordano ampliata da N.S. Papa Alesandro VII and Altra veduta della Piazza di Mte Giordano ampliata da N.Sig. Papa Alessandro VII focus on the Piazza di Monte Giordano and the façade at the northwest corner of the complex (Figures 3 and 4). A looming clock tower tops this façade and overlooks the piazza, situated on a main thoroughfare of the city with vast ceremonial significance.

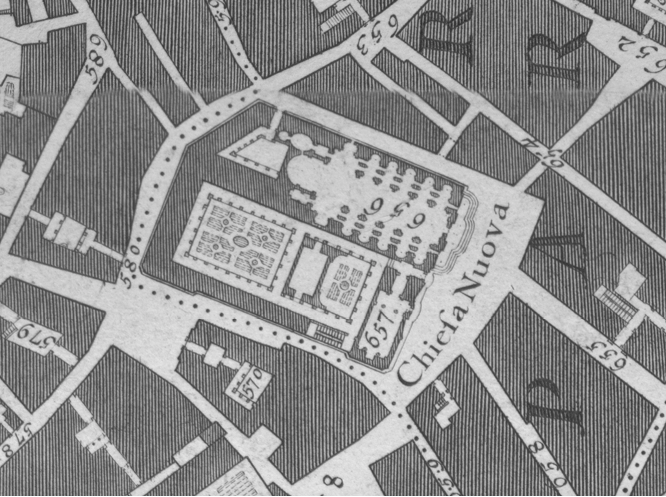

The process of modeling began with a comparison of the block depicted in Falda’s 1676 map (Figure 1) to the same block in Giambattista Nolli’s 1748 measured ichnographic map of Rome (Figure 5). While several minor discrepancies emerged, the general outline of the block remains relatively consistent between Falda and Nolli, allowing for the use of Nolli’s measured outline of the block’s dimensions in the modeling process. The differences between the two maps occur in the number of steps depicted before the façade of S. Maria in Vallicella and the exact number and configuration of the courtyards. The discrepancies in the courtyards likely stem from the block’s placement on the edge of two separate plates in Falda’s map, and may reveal an instance in which Falda intentionally abbreviated or simplified a complicated space. The differing number of steps depicted in front of the church by the two cartographers was an issue that necessitated more attention in the modeling process. Neither of these considerations affected the outer dimensions of Nolli’s block, however, so the later plan could be used as the foundation on which to build a model of Falda’s Chiesa Nuova block.

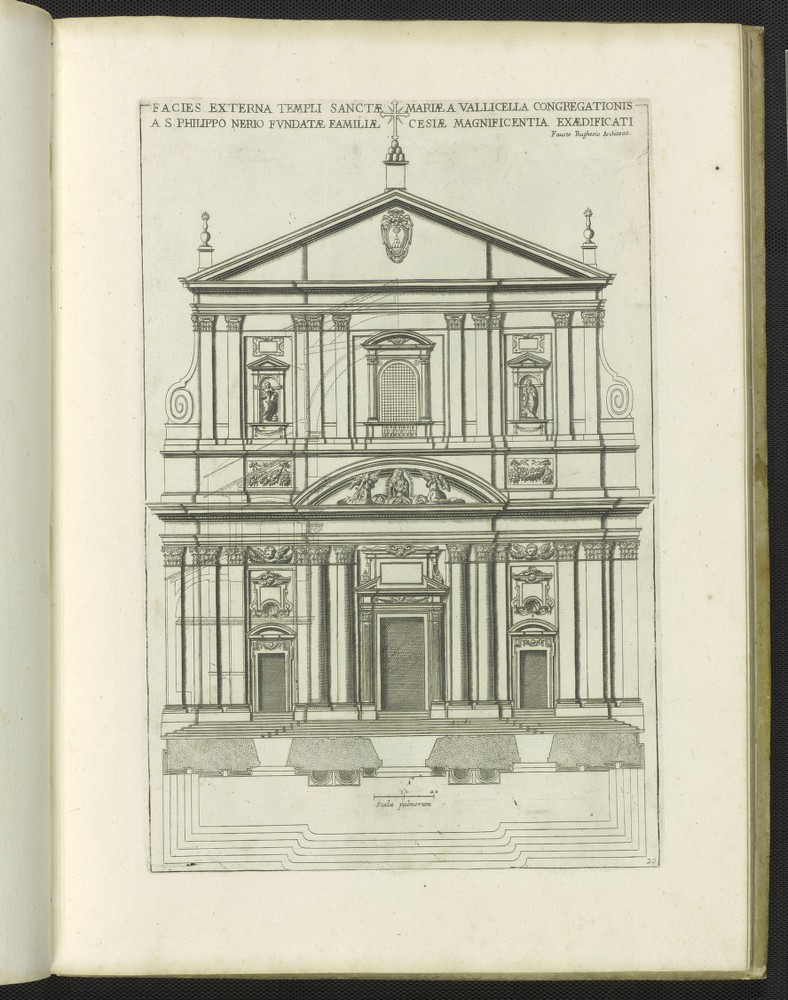

In addition to relevant works by Falda, several additional documents were used in the process of modeling S. Maria in Vallicella. A measured elevation of the church included in Giovanni Giacomo de Rossi’s Insignium Romae templorum prospectus exteriores interioresque: a celebrioribus architectis inventi: nunc tandem suis cum plantis ac mensuris, published in 1684, proved crucial for the modeling of the church’s façade (Figure 6). The scale in palmi included at the bottom of the print made it an invaluable source that provided key measurements for the modeling process. The high level of similarity between the façade as depicted in the Insignium print and in Falda’s view (Figure 2) make the measured Insignium print the best possible source for the recreation of the church’s façade. The present-day appearance of Chiesa Nuova (Figure 7) is virtually identical to the façade recorded in Falda’s view and in the Insignium print, which allowed for the use of modern photographs as additional references in the modeling process.

-

Figure 6: S. Facies externa Templi Sanctae Mariae a Vallicella congregationis a S. Philippo Nerio fundatae familiae Cesiae magnificentia exaedificati, from Insignium Romae templorum prospectus…, 1684. -

Figure 7: Photograph of the Oratory (left) and Chiesa Nuova, or Santa Maria in Vallicella (right).

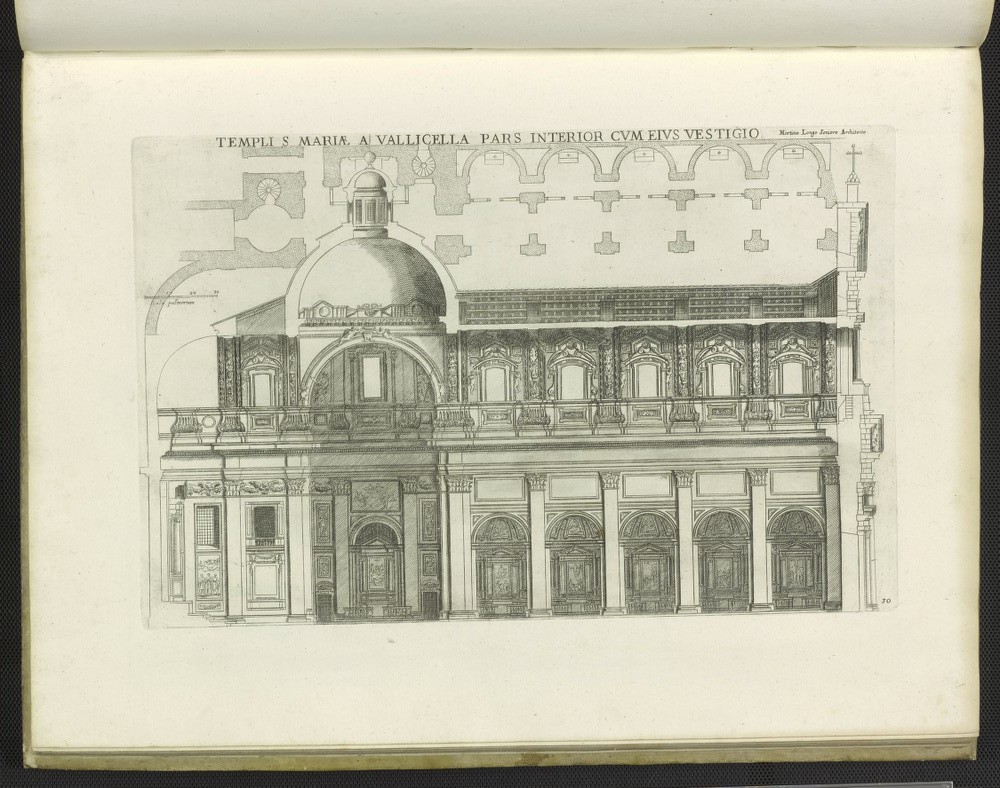

Another print from the same 1684 Insignium Romae templorum volume represents the length of the church in section, again measured with a palmi scale (Figure 8). This document was particularly helpful in the construction of the roof and dome of the church, elements markedly absent in Falda’s view of the façade (Figure 2), but present in his 1676 map (Figure 1). This measured print provided valuable information about the size and placement of the dome and roof structures that Falda’s images do not. While several other early modern sources depict the church’s roof, the only print that includes measured elements and suggests their relationship to the height of the façade is the Insignium print (Figure 8).

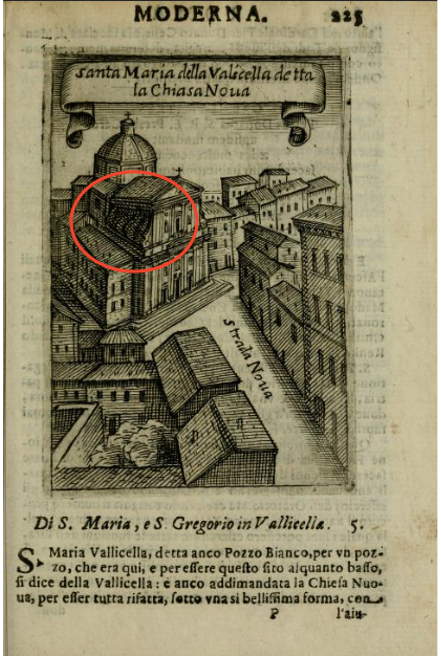

A question that arose during the process of recreating the church concerned the buttress-like supports visible on the church’s roof in several contemporary documents and in modern photographs, but not in Falda’s map (Figure 1) or Nuovo teatro view (Figure 2). While aerial photographs clearly show four trapezoidal buttresses on each side of the clerestory level of the church (Figure 9), they are absent in Falda’s 1676 depiction of the building (Figure 1). Falda does, however, include four window openings. Other visual documents further complicate the issue. At least two other early modern prints show windows on the side of the Chiesa Nuova but no exterior buttressing element.[2] Other sources depict obvious exterior architectural elements. An engraving in the guidebook Ritratto di Roma moderna published in 1638 shows buttresses barely visible beyond the hatched shadow, but here they appear to be curved (Figure 10).[3] Similar ribbed architectural elements are also present in Giuseppe Vasi’s 1756 print of the Chiesa Nuova.[4]

-

Figure 9: Aerial view of S. Maria in Vallicella and surrounding block. -

Figure 10: Santa Maria della Vallicella detta la Chiesa Nuova from Pompilio Rotti, Ritratto di Roma moderna, 1638.

Angular buttresses appear in several early modern sources. Critically, a drawing of the church by Lievin Cruyl (reversed in preparation for a printed image), created just under a decade before Falda’s map and in the same year as his Nuovo teatro view of the building, shows trapezoidal supports between the two facades (Figure 11)[5]. Modern day photographs provide irrefutable evidence for the presence of four trapezoidal buttresses on either side of the building (Figure 9). Despite the competing evidence, due to the apparent presence of angled buttresses in Cruyl’s contemporary drawing of the church and in modern photographs, we decided to include four trapezoid-shaped supports on each side of the church’s nave in the final model of S. Maria in Vallicella.

Another question that arose during the process of converting Falda’s Chiesa Nuova into a digital model had to do with the number of steps represented at the entrance to the church. Falda was consistent in his inclusion of three steps before the Chiesa Nuova façade, as can be observed in both his etched view and his map (Figures 1and 2). Various other sources, however, depict a different number of steps in front of the church. The 1665 drawing by Cruyl and the measured elevation of the church in the Insignium Romae templorum (1684) both show the church with six steps (Figures 6 and 11). Nolli, in his 1748 ichnographic map, depicts four steps in front of S. Maria in Vallicella, the same number that appear in front of the church today. As these documents demonstrate, the actual number of steps present at the time when Falda was completing his etchings remains far from certain, and the configuration of steps likely changed over time as alterations were made to the piazza and platform in front of Chiesa Nuova. Because the goal of the current project is to build Falda’s Rome, we chose to render S. Maria in Vallicella with three steps.

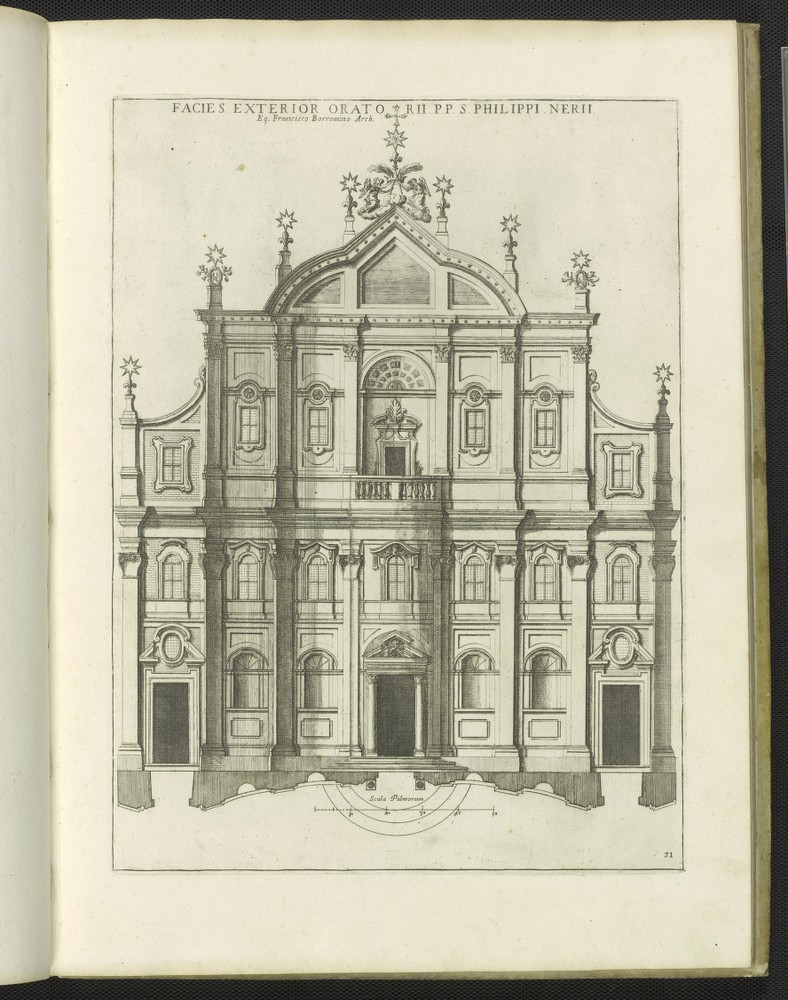

In the process of modelling the neighboring Oratory structure, we again consulted Giovanni Giacomo De Rossi’s 1684 Insignium Romae templorum for a measured image of the Oratory façade with a palmi scale (Figure 12). The print of the façade contained in that volume, however, differs considerably from the façade depicted by Falda in his map, and from the building in its final design and construction (Figures 1, 7). In the Oratory designed and built by Borromini, the five bays that constitute the central, concave portion of the façade are flanked by additional bays. One complete bay stands on the right side and a wider, three-bay unit extends to the left, composed of two windowed bays and another irregular unit that reconciles the corner of the building. The fourth story of the structure has also been filled in above each of these three-storied bays across the length of the building. The façade represented in the Insignium Romae templorum print depicts an idealized version of the final design, distilled to the central unit of five bays and their symmetrical pendants. Visual and textual evidence suggests that Borromini’s original design consisted of only five bays, but the design was altered early in the construction process to reconcile the arrangement of interior spaces beyond the facade.[6]

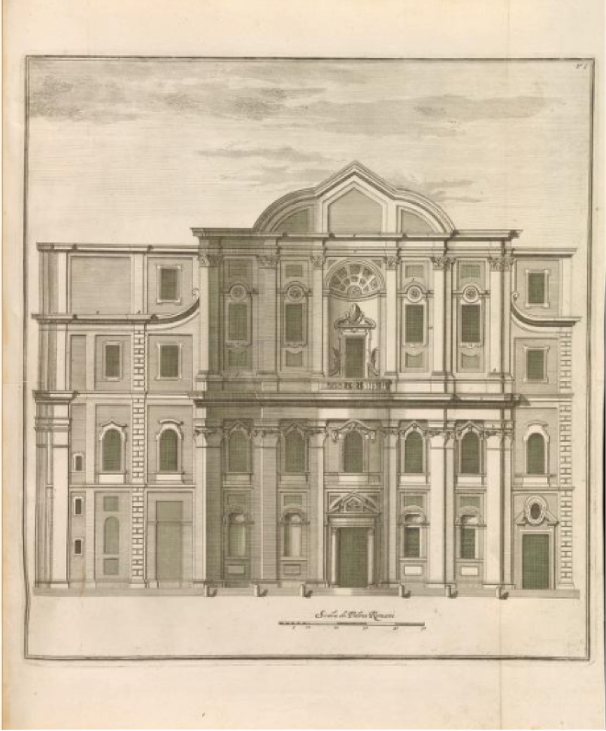

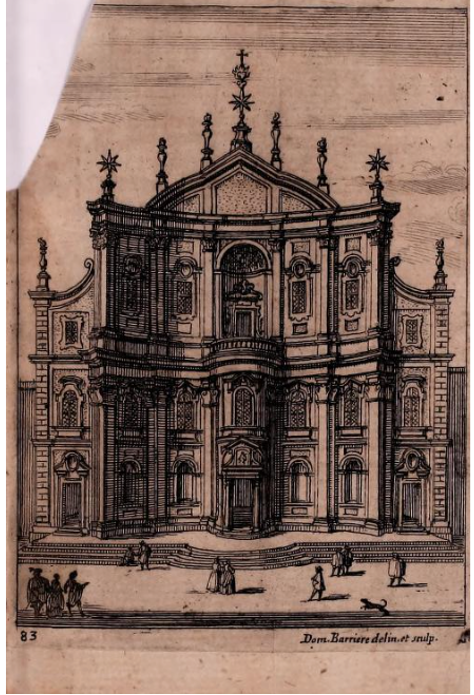

The façade included in the Insignium Romae templorum is remarkably similar to an idealized composition produced by Domenico Barrière in 1660 in which Borromini’s oratory appears as a stand-alone structure isolated from its position within the built environment of the block (Figure 13). The image was published by Sebastiano Giannini in his 1725 book on the Casa dei Filippini, the Opus architectonicum Equitis Francisci Boromini… (plate 5). Begun in the 1640s by Francesco Borromini and Oratorian Virgilio Spada, the book finally published by Giannini in 1725 included some prints that were made during the architect’s lifetime and others made much later.[7] Several views of the Oratory façade appear in the publication, including one that faithfully reproduces the structure as built and features a scale in palmi (plate 6) (Figure 14). This document became the main reference point for obtaining the measurements of specific architectural elements in the modeling process.

-

Figure 13: Print of the Oratory façade by Domenico Barrière (1660), published in Giannini, Opus architectonicum Equitis Francisci Borromini…, 1725. -

Figure 14: Measured print of the Oratory façade, from Giannini, Opus architectonicum Equitis Francisci Borromini…, 1725.

Importantly, the measured Giannini image does not directly correspond to the two versions of the façade etched by Falda, first in his Nuovo teatro view (Figure 2) and then in his map (Figure 1). Rather than directly replicating the built structure as it stood in the 1660s, Falda chose to depict the structure in two different ways. In his veduta of the two facades, Piazza chiesa é oratorio di Santa Maria in Vallicella detta la Chiesa Nova (Figure 2), Falda combined elements of the two prints of the façade examined above. Situated against the leftmost edge of the plate, the Oratory appears in its idealized, isolated guise, similar to Barrière’s 1660 printed version (Figure 13). The strips of large-scale, rusticated brickwork, or quoins, on the façade’s edges do not appear in Barrière’s image, but were a part of the built structure as represented in Giannini’s later measured print (Figure 14). But Domenico Barrière created another image of the Oratory façade that corresponds even more closely with the building that Falda depicts in his veduta. Here, Barrière again represents the Oratory as a more or less freestanding, idealized structure, but also includes the rusticated quoins (Figure 15). This etching was one of three idealized views of the Casa dei Filippini that the artist produced for Fioravante Martinelli’s 1658 edition of the guidebook Roma ricercata nel suo sito, et nella scuola di tutti gli antiquarij.[8] The close correspondence between this image and Falda’s view is given more weight due to the close visual relationship between Falda and Barrière’s depictions of the clock tower façade on the northwest corner of the building (Figures 3 and 16). These similarities suggest that Falda had access to this edition of Martinelli’s guidebook at the time that he was designing the Nuovo teatro prints.

-

Figure 15: Print of the Oratory façade by Domenico Barrière after Francesco Borromini, from Martinelli, Roma ricercata nel suo sito…, 1658. -

Figure 16: Print of the Clocktower façade by Domenico Barrière after Francesco Borromini, from Martinelli, Roma ricercata nel suo sito…, 1658.

In the map that Falda produced for Gian Giacomo de Rossi in the following decade the etcher depicts the Oratory quite differently. A four-story rectangular structure delineated by four evenly spaced bays adjoins his simplified five-bay version of Borromini’s façade (Figure 1). The edifice represented by Falda in his map generally corresponds to the structure as it was finished in the 1660s but is not a completely faithful reproduction of the building. Falda exaggerates the rectangular library that was added to the upper left corner of the façade in c. 1665 (an element not included in his veduta).[9] Because Falda included the fourth story addition in his map, the decision was made to model the complete façade as seen in Giannini’s measured print (Figure 14).

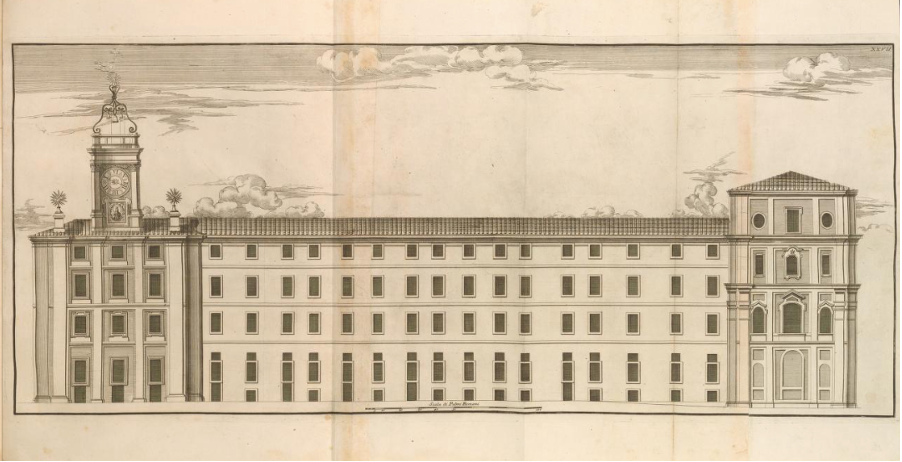

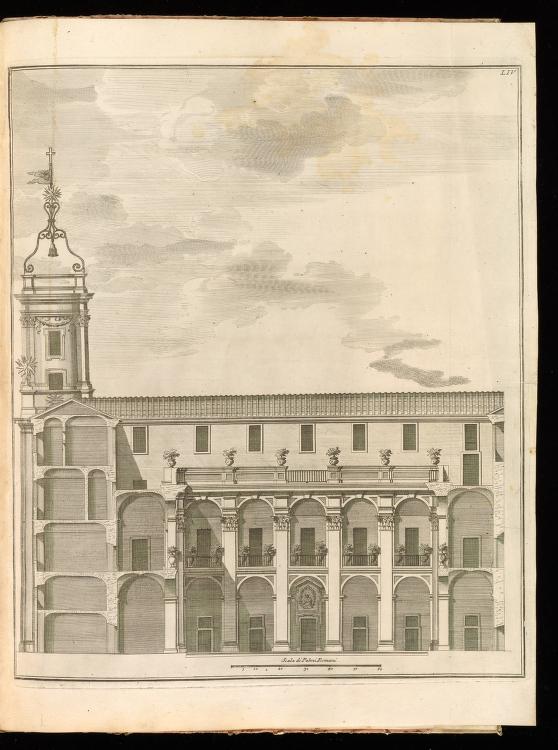

Additional plates from Sebastiano Giannini’s 1725 volume on the Casa dei Filippini provided critical information on other aspects of the building complex. A fold-out elevation of the western length of the block (plate 27), stretching from the clock tower façade on the northwest corner to the side of the Oratory on the south end of the block, proved particularly valuable because of its scale in palmi (Figure 17). From this print we were able to obtain relative elevations for the different sections of the west façade as well as more detailed information regarding its architectural articulation. Some discrepancies appear between Giannini’s image of the clock tower façade and Falda’s representation of the structure in his Nuovo teatro view, Piazza di Monte Giordano ampliata da N.S. Papa Alesandro VII (Figure 3). For example, Falda represents four pilasters of identical thickness on the façade below Borromini’s concave clock tower, while the image published by Giannini includes pilasters of two different widths, the inner pair being substantially thinner than the outer strips. In this instance, our model follows Falda’s representational choices.

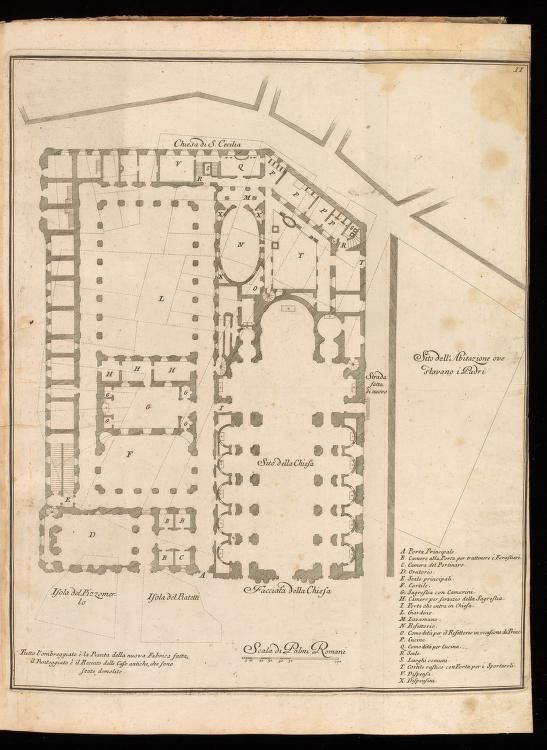

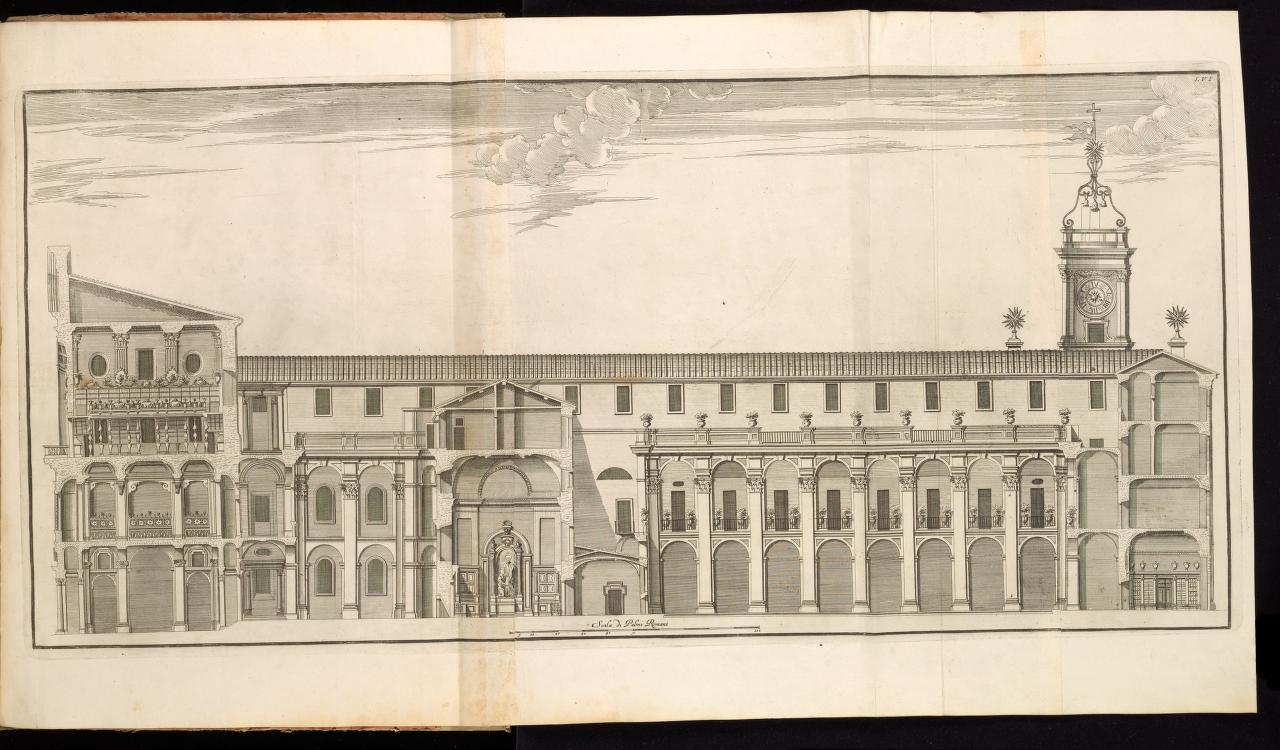

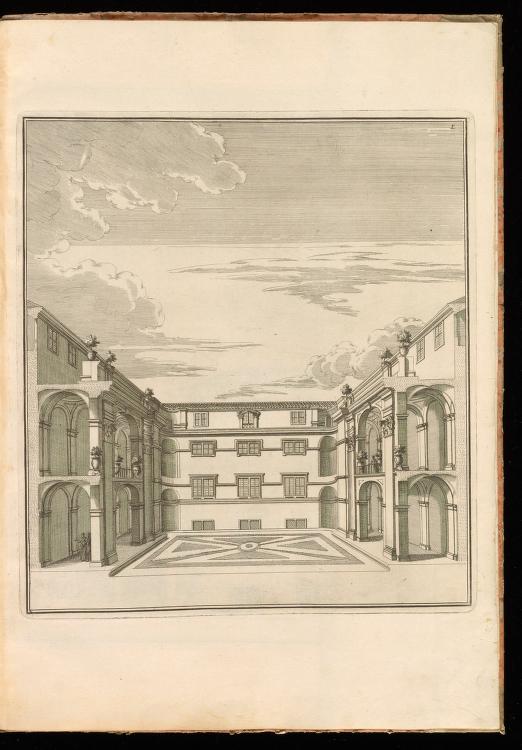

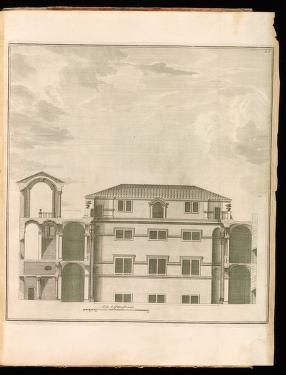

A ground plan from Giannini’s Opus Architectonicum (plate 2) was also consulted during the modeling process (Figure 18). It was particularly useful in rendering the three courtyards contained within the block—the angled court behind the apse of the church, and two larger ones behind the Oratory along the central axis of the Casa dei Filippini. Four other plates from the Opus Architectonicum proved crucial to the digital reconstruction of the Casa dei Filippini’s two interior courtyards. These include a longitudinal section of the western length of the block that highlights the elevation of both courtyards, the smaller first court just beyond the Oratory with its distinctive curving corners and the larger, more rectangular second cortile that stretches toward the clock tower (plate 56) (Figure 19). Plate 54 shows the shorter, north end of the second courtyard in measured elevation (Figure 20), while plates 50 and 51 depict the first court in perspective and measured section/elevation (Figures 21 and 22). Modern photographs supplemented the printed images with details of the courtyards’ rich moldings and other elements of architectural articulation (Figures 23 and 24). Together, early modern printed sources and modern photographs allowed for the creation of a 3D model that reflects the distinctive footprint and ornamental intricacy of the courtyards at the Casa dei Filippini.

-

Figure 20: Casa dei Filippini, second courtyard, from Giannini, Opus architectonicum Equitis Francisci Borromini…, 1725. -

Figure 21: Casa dei Filippini, first courtyard, from Giannini, Opus architectonicum Equitis Francisci Borromini…, 1725.

-

Figure 22: Casa dei Filippini, first courtyard, from Giannini, Opus architectonicum Equitis Francisci Borromini…, 1725. -

Figure 23: Photograph of Casa dei Filippini, first courtyard.

[1] For an in-depth account of the building of the Chiesa Nuova and the Oratory and Casa dei Filippini, see especially Connors 1980; Blunt 1982, 114-119.

[2] A roof structure similar to the one depicted in Falda’s map appears in Giovanni Maggi’s earlier map of Rome, first printed in 1625. For Maggi’s 1625 map see http://img.biblhertz.it/jquery/digilib.html?fn=piantediroma/00087-1625_Maggi_Giovanni_BNCVE_18_P_A_1-2. Four windows also appear in place of buttresses in a mid eighteenth-century view by Giovanni Battista Piranesi of the Oratory and Chiesa Nuova facades. For Piranesi’s print see https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1923-0209-1-51.

[3] Totti 1638, 225.

[4] For Vasi’s print of S. Maria in Vallicella see http://vasi.uoregon.edu/catalog/appendix/vn137.html.

[5] While the original 1593 version of Antonio Tempesta’s map of Rome shows S. Maria in Vallicella with four clerestory windows and no buttresses, the updated 1645 edition published by Giovanni Giacomo de Rossi depicts the church with angular buttresses. For the 1593 edition of Tempesta’s map see http://libris.kb.se/bib/22447939. For the 1645 edition see https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/381436.

[6] Connors 1980, 220-223, Cat. 41.

[7] Borromini, Connors, and Spada 1998. See especially pages LXXIX-LXXXI of Connors’ Introduction on Sebastiano Giannini’s 1725 volume.

[8] See Borromini, Connors, and Spada 1998, Introduction LIV.

[9] Connors 1980, 56 and 278, Cat. 101.

Figures:

- Figure 1: Giovanni Battista Falda. 1676. Nuova pianta et alzata della città di Roma con tutte le strade, piazze et edificii de tempi, palazzi, giardini et altre fabbriche antiche e modern come si trovano al presente nel pontificato di N.S. Papa Innocentio XI con le loro dichiarationi nomi et indice copiosissimo. Collection of Vincent J. Buonanno (artwork in the public domain, photograph Copyright All Rights Reserved Vincent J. Buonanno).

- Figure 2: Giovanni Battista Falda. “Piazza chiesa é oratorio di Santa Maria in Vallicella detta la Chiesa Nova” in Il nuovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna, vol. 1. print 21. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photography provided by Emory University Readux https://readux.ecds.emory.edu/books/readux:t2b5p/pages/readux:t2cs8/).

- Figure 3: Giovanni Battista Falda. “Piazza di Monte Giordano ampliata da N.S. Papa Alesandro VII” in Il nuovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna, vol. 1. print 22. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photography provided by Emory University Readux https://readux.ecds.emory.edu/books/readux:t2b5p/pages/readux:t2cvj/)

- Figure 4: Giovanni Battista Falda. “Altra veduta della Piazza di Mte Giordano ampliata da N.Sig. Papa Alessandro VII” in Il nuovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna, vol. 1. print 23. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photography provided by Emory University Readux https://readux.ecds.emory.edu/books/readux:t2b5p/pages/readux:t2cxt/).

- Figure 5: Giambattista Nolli. 1748. La pianta grande di Roma. Collection of the Yale University Art Gallery. The Arthur Ross Collection. 2012.159.8.1-.6 (artwork in the public domain, photograph Public Domain provided by Yale University Art Gallery https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/177965)

- Figure 6: Giovanni Giacomo De Rossi. “Facies externa Templi Sanctae Mariae a Vallicella congregationis a S. Philippo Nerio fundatae familiae Cesiae magnificentia exaedificati” in Insignium Romae templorum prospectus exteriores interioresque: a celebrioribus architectis inventi: nunc tandem suis cum plantis ac mensuris. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Emory University Readux https://readux.ecds.emory.edu/books/readux:th936/pages/readux:thc7z/).

- Figure 7: Photograph by Abbey Hafer (artwork CC-BY, photograph provided CC-BY by Abbey Hafer).

- Figure 8: Giovanni Giacomo De Rossi. “Templi S Mariae a Vallicella pars interior cum eius vestigio” in Insignium Romae templorum prospectus exteriores interioresque: a celebrioribus architectis inventi: nunc tandem suis cum plantis ac mensuris. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Emory University Readux https://readux.ecds.emory.edu/books/readux:th936/pages/readux:thc97/).

- Figure 9: Google maps aerial view of S. Maria in Vallicella and surrounding block. (imagry copyright Google Maps 2021, map available via Google Maps online https://goo.gl/maps/pfQpSVHdwopxBYLP6).

- Figure 10: Pompilio Totti. 1638. Ritratto di Roma moderna. Rome. Collection of Archive.org (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org and scanned by Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/details/ritrattodiromamo00tott/page/223/mode/thumb).

- Figure 11: Lieven Cruyl. 1664. Eighteen Views of Rome. Collection of The Cleveland Museum of Art, Dudley P. Allen Fund 1943.267 (artwork in the public domain, photograph Creative Commons (CC0 1.0) by The Cleveland Museum of Art online https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1943.267).

- Figure 12: Giovanni Giacomo De Rossi. “Facies exterior Orato RII.P.P. S. Philippi Nerii” in Insignium Romae templorum prospectus exteriores interioresque: a celebrioribus architectis inventi: nunc tandem suis cum plantis ac mensuris. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Emory University Readux https://readux.ecds.emory.edu/books/readux:th936/pages/readux:thcch/).

- Figure 13: Sebastiano Giannini. 1725. Opus architectonicum Equitis Francisci Borromini… plate 5. Rome. Collection of Archive.org (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org and scanned by Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/).

- Figure 14: Sebastiano Giannini. 1725. Opus architectonicum Equitis Francisci Borromini… plate 6. Rome. Collection of Archive.org (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org and scanned by Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/).

- Figure 15: Fioravante Martinelli. 1658. Roma ricercata nel suo sito…3rd ed. Rome. Collection of Archive.org (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org and scanned by Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/).

- Figure 16: Fioravante Martinelli. 1658. Roma ricercata nel suo sito…3rd ed. Rome. Collection of Archive.org (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org and scanned by Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/).

- Figure 17: Sebastiano Giannini. 1725. Opus architectonicum Equitis Francisci Borromini… plate 27. Rome. Collection of Archive.org (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org and scanned by Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/).

- Figure 18: Sebastiano Giannini. 1725. Opus architectonicum Equitis Francisci Borromini… plate 2. Rome. Collection of Archive.org (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org and scanned by Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/).

- Figure 19: Sebastiano Giannini. 1725. Opus architectonicum Equitis Francisci Borromini… plate 56. Rome. Collection of Archive.org (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org and scanned by Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/).

- Figure 20: Sebastiano Giannini. 1725. Opus architectonicum Equitis Francisci Borromini… plate 54. Rome. Collection of Archive.org (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org and scanned by Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/).

- Figure 21: Sebastiano Giannini. 1725. Opus architectonicum Equitis Francisci Borromini… plate 50. Rome. Collection of Archive.org (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org and scanned by Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/).

- Figure 22: Sebastiano Giannini. 1725. Opus architectonicum Equitis Francisci Borromini… plate 51. Rome. Collection of Archive.org (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org and scanned by Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/).

- Figure 23: Photograph by Abbey Hafer (artwork CC-BY, photograph provided CC-BY by Abbey Hafer).

- Figure 24: Photograph by Abbey Hafer (artwork CC-BY, photograph provided CC-BY by Abbey Hafer).

Short Bibliography

- Barbieri, Costanza, Sofia Barchiesi, and Daniele Ferrara. 1995. Santa Maria in Vallicella, Chiesa Nuova. Rome: Fratelli Palombi Editori.

- Blunt, Anthony. 1979. Borromini. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Blunt, Anthony. 1982. Guide to Baroque Rome. New York: Harper & Row Publishers.

- Borromini, Francesco, Joseph Connors, and Virgilio Spada. 1998. Opus Architectonicum. Milano: Il Polifilo.

- Borromini, Francesco. 2009. Borromini’s Book, The ‘Full Relation of the Building’ of the Roman Oratory by Francesco Borromini and Virgilio Spada of the Oratory. Translated with a commentary by Kerry Downes. Wetherby: Oblong Creative Ltd.

- Ceen, Allan. 1977. “The Quartiere de’Banchi: Urban Planning in Rome in the First Half of the Cinquecento.” PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania.

- Connors, Joseph. 1980. Borromini and the Roman Oratory: Style and Society. New York; Cambridge: The Architectural History Foundation and The MIT Press.

- Connors, Joseph. 1989. “Alliance and Enmity in Roman Baroque Urbanism.” Römisches Jahrbuch der Bibliotheca Hertziana 25: 207-294.

- Falda, Giovanni Battista, and Giovanni Giacomo De Rossi. 1665-1669. Il nuovo teatro delle fabbriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna. 3 vols. [Roma]: Giovanni Giacomo De Rossi.

- Falda, Giovanni Battista, and Giovanni Giacomo De Rossi. 1676. Nuova pianta et alzata della citta de Roma con tutte le strade piazza et edificii de tempii : palazzi, giardini et altre fabbriche antiche e moderne come si trovano al presente nel pontificato di N.S. papa Innocentio XI con le loro dichiarationi nomi et indice copiosissimo. Roma: de Rubeis.

- Giannini, Sebastiano. 1725. Opus architectonicum equitis Francisci Boromini: ex ejusdem exemplaribus petitum Oratorium nempè aedesque Romanæ RR. PP. Congregationis Oratorii S. Philippi Nerii. Roma.

- Maggi, Giovanni. 1625. Icnografia della Citta di Roma… retrieved from CIPRO: http://fmdb.biblhertz.it/cipro/CIPROinfoeng.htm

- Martinelli, Fioravante. 1658. Roma ricercata nel suo sito, et nella scuola di tutti gli antiquarij. 3rd edition. Roma: A spese di Biagio Deuersin libraro …

- Pericoli Ridolfini, Cecilia. 1977. Guide Rionali di Roma, Rione VI-Parione, Parte II. Rome: Fratelli Palombi Editori.

- Rossi, Giovanni Giacomo de. 1684. Insignium Romae templorum prospectus exteriors interioresque : a celebrioribus architectis inventi : nunc tandem suis cum plantis ac mensuris. [Rome]: Jo[sephus] Jacobo de Rubeis …

- Tempesta, Antonio and Giacomo Bosios. 1593. Recens provt hodie iacet almae urbis Romae cum omnibvs viis aedificiisque prospectvs accvratissimae delineatvs. Roma.

- Tice, Jim. The Interactive Nolli Map Website. Department of Architecture and InfoGraphics Lab, Department of Geography, University of Oregon 2005. Available from http://nolli.uoregon.edu/.

- Totti, Pompilio. 1638. Ritratto di Roma moderna. Roma: Per il Mascardi, ad instanza di Pompilio Totti.

Leave a Reply