Reconstructing the Piazza del Popolo

by Joanna Mundy

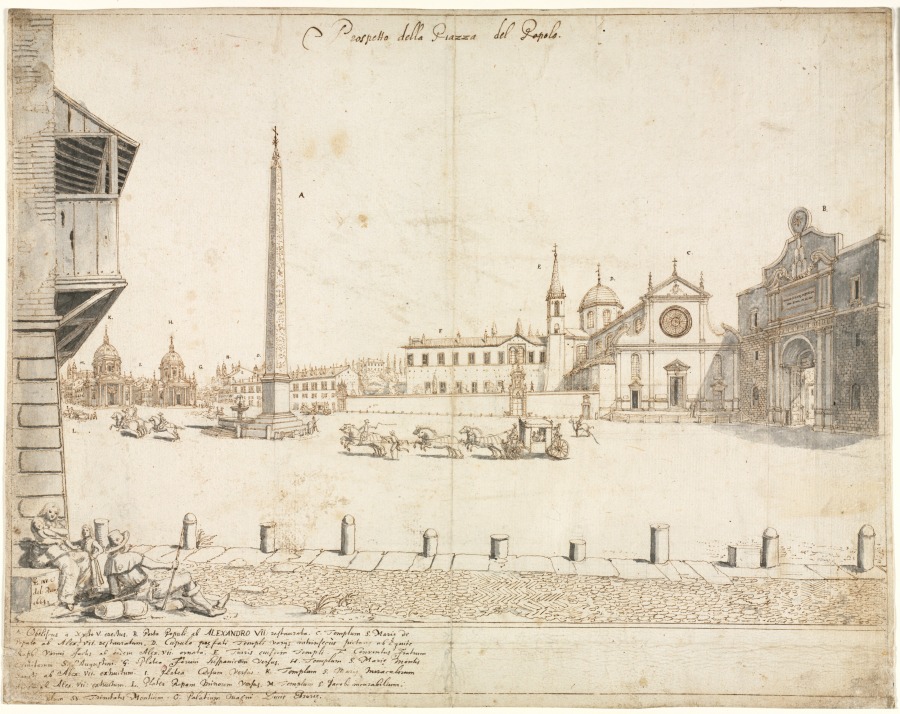

In order to reconstruct the Piazza del Popolo ca. 1676, we began by studying the three prints of this urban space made by Giovanni Battista Falda. These prints include Fontana su la Piazza della Porta del Popolo sotto la Guglia, from Le fontane di Roma nelle piazze e luoghi publici della città, con li loro prospetti, come sono al presente (Figure 1), and Piazza del’Popolo abbellita da N.S. Papa Alesandro VII and Altra veduta della Piazza del’Popolo entrandosi nella citta from Il nuovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna, vol. 1, prints 6 and 7 (Figures 2 and 3).[1]

-

Figure 2: G.B. Falda, Piazza del’Popolo abbellita da N.S. Papa Alesandro VII, 1665.

-

Figure 3: G.B. Falda, Altra veduta della Piazza del Popolo entrandosi nella citta, 1665.

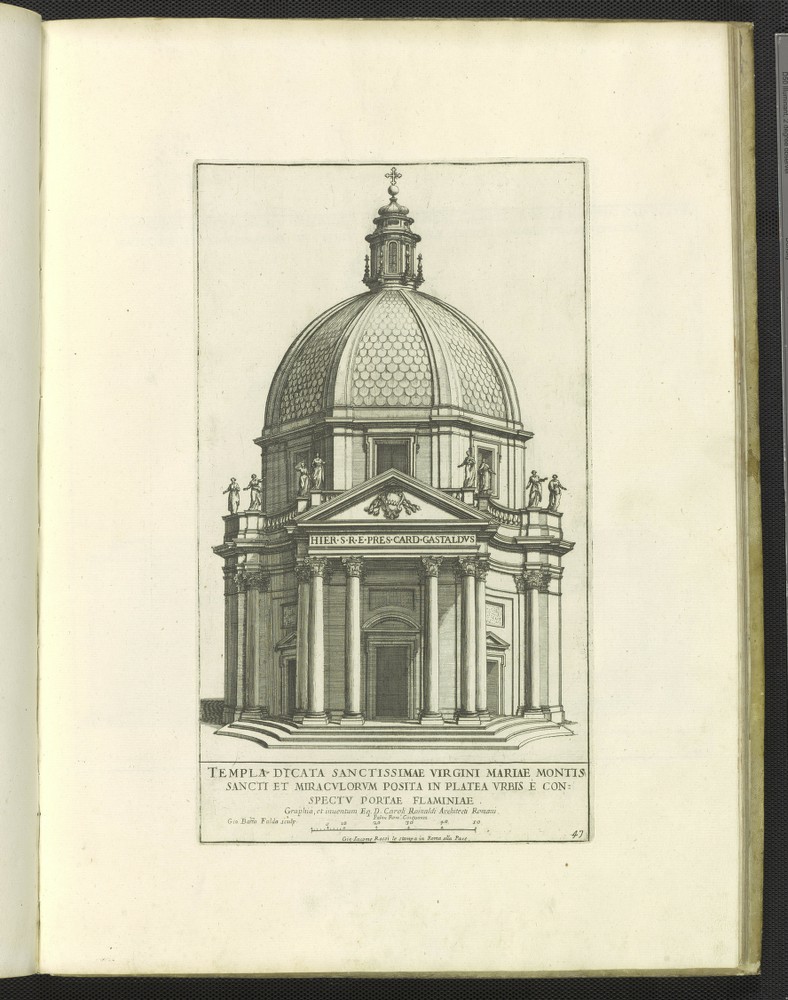

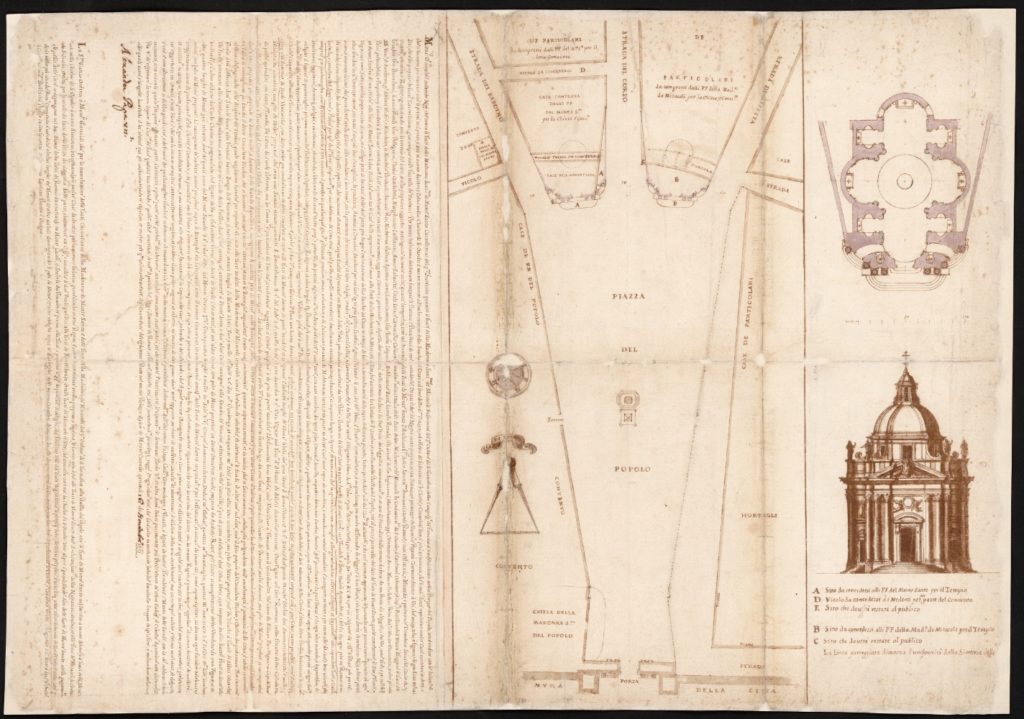

Additionally, we used the print Templa dicata Sanctissimae Virgini Mariae Montis Sancti et Miraculorum posita in platea urbis è conspectu Portae Flaminiae, etched by Falda for Giovanni Giacomo De Rossi’s Insignium Romæ templorum prospectus exteriores interioresque: a celebrioribus architectis inventi: nunc tandem suis cum plantis ac mensuris, 1684, as the primary source for the reconstruction of the twin churches (Figure 4).[2]

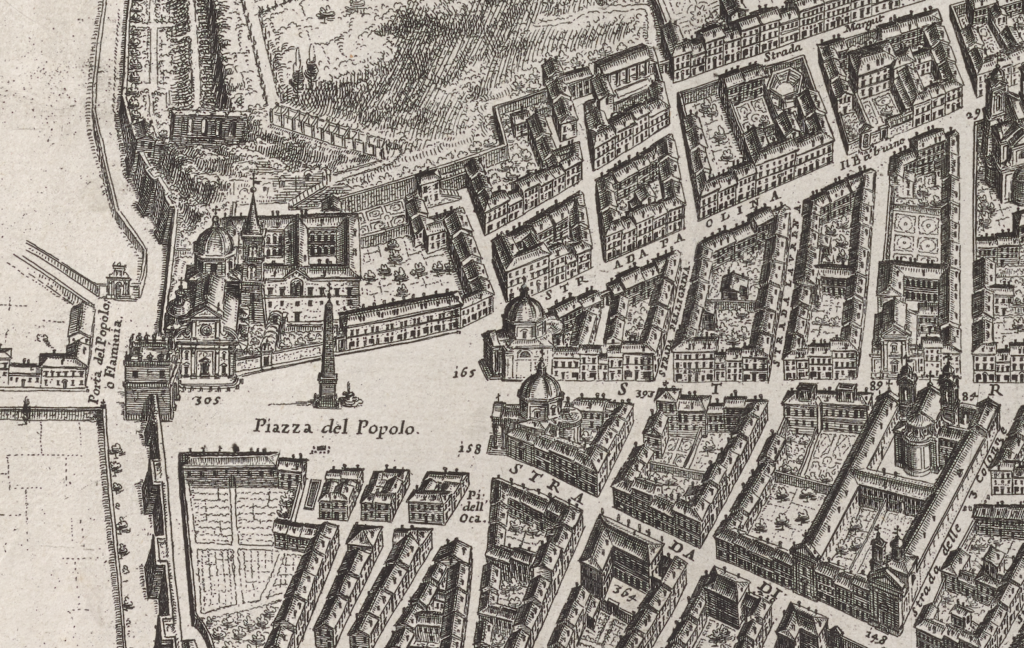

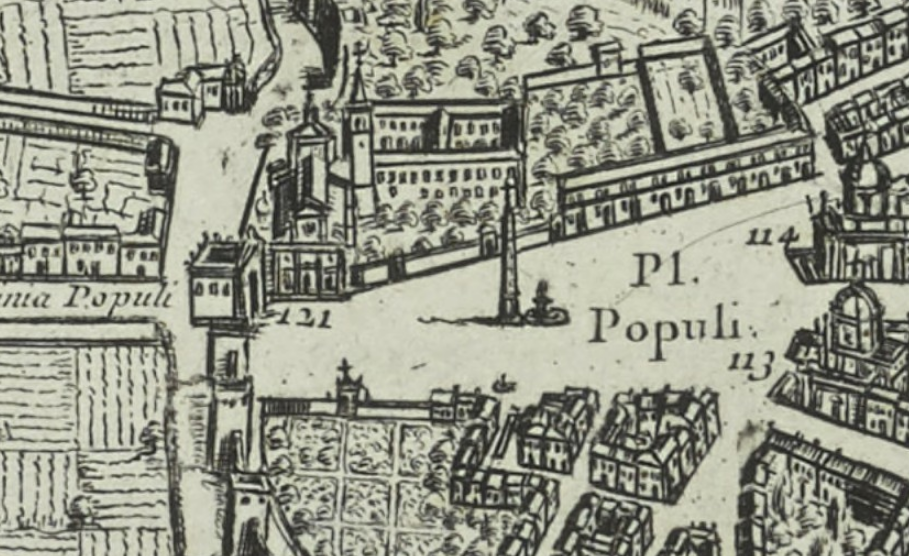

We reconciled the details in these images with the depiction of the piazza in Falda’s 1676 map Nuova pianta et alzata della città di Roma con tutte le strade, piazze et edificii de tempi, palazzi, giardini et altre fabbriche antiche e moderne come si trovano al presente nel pontificato di N.S. Papa Innocentio XI con le loro dichiarationi nomi et indice copiosissimo (Figure 5).[3] In cases where the buildings, fountains, and other elements were consistent in both prints and map, we favored the prints as our primary source as they were far more detailed. The prints, Fontana su la Piazza della Porta del Popolo sotto la Guglia, and Piazza del’Popolo abbellita da N.S. Papa Alesandro VII, were therefore the primary sources for the detailed reconstruction of the water trough fountains and the surrounding streets, plants, and buildings on the west side of the piazza. Where we found discrepancies between the prints and the 1676 map, we researched the changes that took place in the area in those years and followed the image we considered to most closely represent the piazza in 1676.

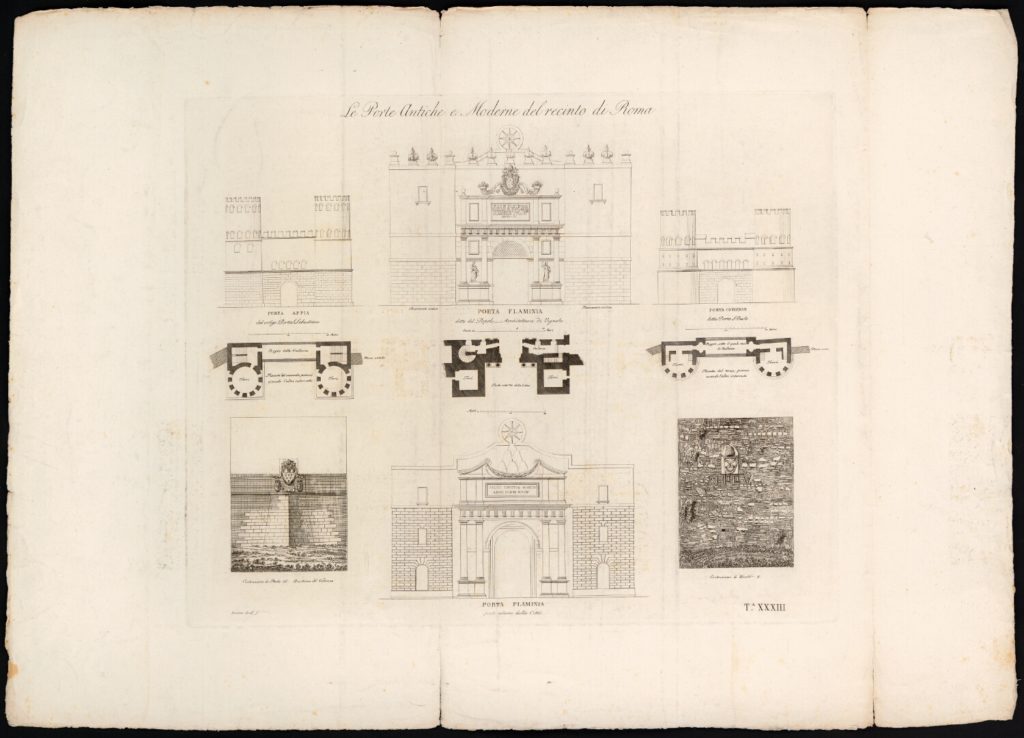

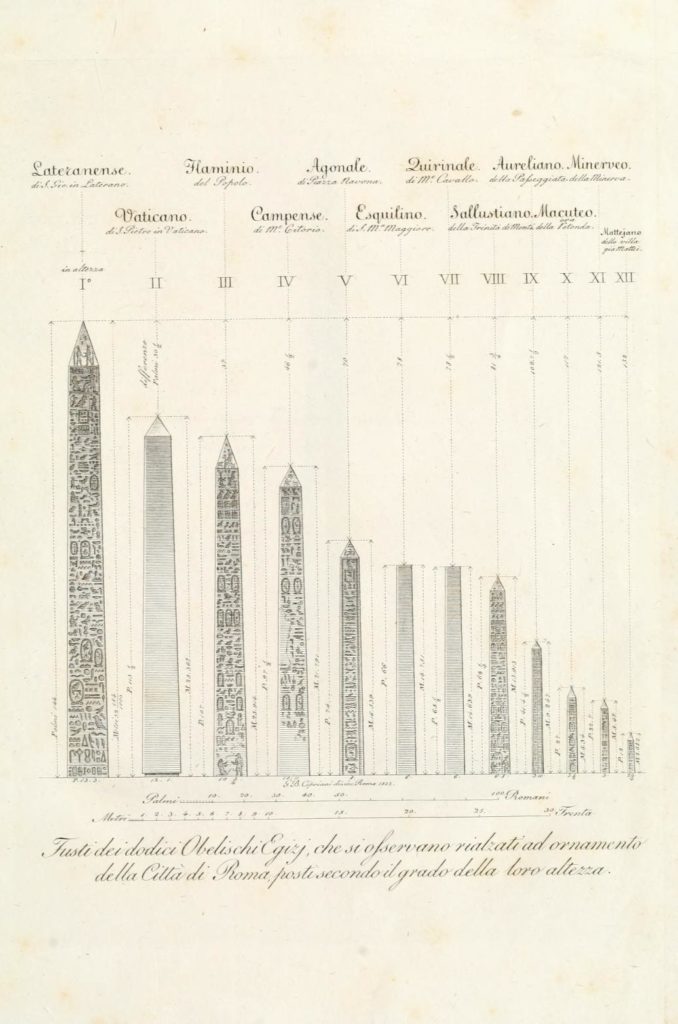

Multiple questions arose in the process of confirming accuracy for the model in relation to the structures in the Piazza del Popolo. There were two questions of scale. First, what was the scale of the Porta del Popolo? We located an historical text with measured drawings of the gates of the city of Rome: Luigi Rossini, Le porte antiche e moderne del recinto di Roma con le mura, prospetti e piante geometriche disegnate ed incise dall’architetto, 1829.[4] The image was scanned and sent to the modelers, and this was used to set the scale of the Porta del Popolo (Figure 6). The second question involved the scale of the obelisk in the center of the piazza. In the first published version of the model, the obelisk was scaled visually by height to match its relative perceived height in Falda’s prints (Figures 2 and 3).[5] In a future version of the model we will use the measured height of the physical obelisk. For the scale of the obelisk in the Piazza del Popolo, we located a print published by Giovanni Battista Cipriani in his Sui dodici obelischi egizj che adornano la città di Roma of 1823, which shows the twelve Egyptian Obelisks of Rome with measured scales (Figure 7).[6] We will compare the true scale of the measured obelisk to the perceived scale represented in Falda’s prints (Figures 2 and 3), and make a decision about how much to adjust the model. Through our research on the height of the obelisk, we noticed that a change has taken place in the depth of the center of the Piazza del Popolo. In Falda’s prints from Il nuovo teatro and Le fontane di Roma the obelisk stands on a rectangular pedestal base formed of three expanding sections. This base sits directly on the ground in the piazza (Figures 1, 2, and 3). In today’s Piazza del Popolo, however, a base of the same shape formed of three expanding rectangular sections sits on top of a platform that is raised by 5 smaller steps and a sixth larger step the height of a bench above the piazza’s paving. The ground level of the piazza was lowered and the fountain moved with the implementation of Luigi Valadier’s redesign in 1816.[7]

-

Figure 6: Scaled drawing of the Porta del Popolo from Le porte antiche e moderne del recinto di Roma, 1829. -

Figure 7: Scaled drawing of the Piazza del Popolo obelisk from G.B. Cipriani’s, Su i dodici obelischi egizj che adornano la città di Roma, 1823.

In addition to scale, questions arose about the sequence and date of construction of the buildings facing the piazza. The long building on the northwest side was added at some point in the seventeenth century, replacing the wall of a large garden. The long building still can be seen in the 1818 Catasto urbano di Roma, Rione IV, foglio I on the northwest side of the piazza before the full implementation of Luigi Valadier’s redesign, which had already begun on the opposite side of the piazza by this date (Figure 8).

Two of the three Falda prints of the Piazza del Popolo, Fontana su la Piazza della Porta del Popolo sotto la Guglia, from Le fontane di Roma nelle piazze e luoghi publici della città, con li loro prospetti, come sono al presente (Figure 1), and Piazza del’Popolo abbellita da N.S. Papa Alesandro VII from Il nuovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna, vol. 1, print 7 (Figure 2), show the earlier garden wall in this position not the seventeenth century long building. The 1676 map, however, shows the long building in this position (Figure 5). The question of when this wall became a building was the most complicated for this piazza. The area no longer exists due to the nineteenth-century renovation of the piazza.[8] There were multiple stages in the process of regularizing the shape of the piazza; we attempted to determine which is represented in the 1676 map. We also attempted to determine if the actual state or a planned building is represented.

![Pianta realizzata a china. Sul verso: "[Pia]nta de la piaza del popolo in Roma".](https://www.baroquerome.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Archivio_CollezioneI_81-280_1.jpg)

Figure 10: Plan of the piazza del Popolo. MSS Vat.lat. 13442. pt. 2. 34r.

See image at the following URL: https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.lat.13442.pt.2/0032

Images Copyright Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

A plan to reorganize the piazza into a funnel shape, originally designed by Carlo Rainaldi, was begun in 1661 under Alexander VII (Figures 9-11). This plan would have adjusted the orientation of the garden wall to mirror the shape established by structures at the eastern side of the piazza. The focus of the plan was the twin churches at the end of the piazza (Figure 9). Carlo Cartari noted in his diary in 1657 that there would be construction in the area of the piazza’s garden, in addition to the twin churches.[9] The design for the piazza shape and related churches continued to change on the advice of Bernini and Fontana at some point in 1662.[10] The project progressed with the aim of regularizing the Piazza del Popolo for the holy year of 1675, though some of the work concluded five years later.[11] This may be the period in which the choice was made to construct the building on the site of the garden wall to regularize the piazza. The property boundary did not shift, however, as had been suggested in previous plans to make the piazza symmetrical. Leaving the property boundary in place may have been a compromise resulting from pressure to meet the deadline of 1675. An engraving by Gaspar van Wittel from 1681 in Cornelis Meijer’s L’arte di restituire à Roma la tralasciata nauigatione del suo Teuere (Figure 12) shows the building on the NW side of the piazza, and the matching structure on the SE side of the piazza already constructed.[12]

A work in pen and ink with wash by Lievin Cruyl of the Piazza del Popolo from 1664 show a version of the twin churches, artificially complete (Figure 13).[13] It also shows the rectangular building on the SE side of the piazza, and the trough fountain to the west as seen in Falda’s print. The image is drawn from the NW end of the piazza, however, and does not show the area that would contain the garden wall or building. A sliver of a wall on the right border of the print may indicate the building.[14] Alveri in 1660 describes this area to the west of the Piazza del Popolo saying “tutto questo tratto è habitatione di gente povera, e per la maggior parte occupato da fenili; & in somma non hà cosa in se degna di memoria.”[15] He does not specifically mention the garden, but rather describes the streets in the area.

It is difficult to determine exactly when the garden wall was replaced with a building, but it appears to have occurred in the late seventeenth century. Falda’s earlier two-plate map of Rome from circa 1667, Recentis Romae ichnographia et hypsographia sive planta et facies ad magnificentiam qua sub Alexandro VII P.M. urbs ipsa directa exculta et decorata est, clearly shows the garden wall (Figure 14).[16] The map of Matteo Gregorio De Rossi and Lievin Cruyl from 1668 also shows the garden wall. The print by G. van Wittel suggests that the rectangular building was in place by 1681, and the slightly prospective drawing by Lievin Cruyl suggests that it was expected by 1664, though the inclusion of the building fragment may have been artistic convention (Figure 13). Falda’s print Fontana su la Piazza della Porta del Popolo sotto la Guglia, while created ca. 1675 and published ca. 1691, may reflect the artist’s use of an earlier source in depicting the garden wall. While it is not certain that the building was complete in 1676, the structure at the very least was expected in the very near future and may well already have been in place, as seen on the map.

[1] Falda, Venturini, and De Rossi 1691; Falda and De Rossi 1665, prints 6 and 7.

[2] Rossi 1684, print 47.

[3] Falda and Rossi 1676, map.

[4] Rossini 1829, Tavole XXXII and XXXIII.

[5] This height was hosted online on baroquerome.org as of 5/6/2019.

[6] The image of this print was reprinted in the book Egitto a Roma: Obelischi. Carnevali and Cirocchi 2004, fig. 22; Cipriani 1823, tav. 2.

[7] Ashby notes the impact the lowering of the piazza level had on the plan and feel of the place. Ashby and Pierce 1924, 94-95.

[8] Ciucci 1974; Ashby and Pierce 1924, 90. The oval design was carried out between 1816 and 1820.

[9] Cartari states that Nel mese di aprile era quasi compito il restauramento della Chiesa del Popolo . . . aggiustati li scalini, acciò resta più spaliar la piazza di quella parte ; e rimodernare, e restaurare, che ne havevano bisogno ; si dipinge la cuppola . . . si restaura il muro del convento contigua alla chiesa in piazza ; si dice si faranno dui chiese alla Vergine M. nelli dui prospetti di detta piazza, una alla SS. Vergine di Monte Santo, l’altro all SS. Vergine de’ Miracoli, chiese piccole hora, ivi vicine. Si dice, si faranno anco edificij nel sito degl’horti di detta piazza. Gerhard Eimer transcribes and quotes this passage from the Cartari Febei archive (ASR, Cartari Febei, 191, f. 10v., 1657) Eimer 1970, 538.

[10] Krautheimer and Jones 1975, 216; Ciejka 2011, 33-38.

[11] Hager 1967/1968, 239-277; Golzio 1941, 127, 130. An inscription on the interior above the door indicates that the church was completed in 1675, but the priest Cervini states that the church did not open until 3 September 1678. Hempel 1919, 48.

[12] Meijer 1685, 157-159.

[13] Hager 1967/1968, 206-207.

[14] http://www.clevelandart.org/art/1943.261

[15] Alveri 1664, 42.

[16] Falda 1667.

Figures:

- Figure 1: Falda, Giovanni Battista. “Fontana su la Piazza della Porta del Popolo sotto la Guglia.” in Le fontane di Roma nelle piazze e luoghi publici della città, con li loro prospetti, come sono al presente. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Emory University Readux).

- Figure 2: Falda, Giovanni Battista. “Piazza del’Popolo abbellita da N.S. Papa Alesandro VII.” in Il nuovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna, vol. 1. print 6. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Emory University Readux).

- Figure 3: Falda, Giovanni Battista. “Altra veduta della Piazza del’Popolo entrandosi nella citta.” in Il nuovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna. vol. 1. print 7. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Emory University Readux).

- Figure 4: De Rossi, Giovanni Giacomo. “Templa dicata Sanctissimae Virgini Mariae Montis Sancti et Miraculorum posita in platea urbis è conspectu Portae Flaminiae.” in Insignium Romæ templorum prospectus exteriores interioresque: a celebrioribus architectis inventi: nunc tandem suis cum plantis ac mensuris. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Emory University Readux).

- Figure 5: Falda, Giovanni Battista. 1676. Nuova pianta et alzata della città di Roma con tutte le strade, piazze et edificii de tempi, palazzi, giardini et altre fabbriche antiche e moderne come si trovano al presente nel pontificato di N.S. Papa Innocentio XI con le loro dichiarationi nomi et indice copiosissimo. Collection of Vincent Buonanno (artwork in the public domain, photograph Copyright All Rights Reserved Vincent Buonanno).

- Figure 6: Le porte antiche e moderne del recinto di Roma con le mura prospetti e piante geometriche disegnate ed incise dall’architetto Luigi Rossini ravennate. Roma. Pubblicate nell’anno MDCCCXXIX. Con privilegio pontificio, con un breve cenno istorico antiquario. 19-22: particolari architettonici di chiesa n.i. Collection of the Archivio di Stato. Collezioni disegni e mappe – Collezione I – Segnatura: 77 – 206 / 1 (artwork in the public domain, photograph copyright Archivio di Stato).

- Figure 7: Cipriani, Giovanni Battista. 1823. Su i dodici obelischi egizj che adornano la città di Roma. Roma: Presso A. Ceracchi. Collection of Archive.org (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org and scanned by Getty Research Institute).

- Figure 8: Presidenza generale del censo. 1818. Catasto urbano di Roma, Rione IV, foglio I. Collection of the Archivio di Stato di Roma Collezioni Catasto Urbano (artwork in the public domain, photograph copyright Archivio di Stato).

- Figure 9: Presidenza delle strade. Piazza del Popolo con le due chiese gemelle. Collection of the Archivio di Stato di Roma Collezioni disegni e mappe – Collezione I Segnatura: 81 – 280 / 1 (artwork in the public domain, photograph copyright Archivio di Stato).

- Figure 10: Under copyright: MSS Vat.lat. 13442. pt. 2. 34r. See image at the following URL: https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.lat.13442.pt.2/0032 Collection Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (artwork in the public domain, photograph images Copyright Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana).

- Figure 11: Presidenza delle strade-Chirografi. 1661/11/16. Plan of the piazza del Popolo Produttore: Sottoscrizioni: Benedetto XIV, pontefice; Vincenzo Ottaviani, notaio del Tribunale delle Strade. Collection of the Archivio di Stato di Roma. Collezioni disegni e mappe – Collezione I Segnatura: 81 – 279 / 1 (artwork in the public domain, photograph copyright Archivio di Stato).

- Figure 12: van Wittel, Gaspar. 1681. “Prospettiva della rinominata piazza e Guglia del Popolo” in Cornelis Meijer. 1685. L’arte di restituire à Roma la tralasciata nauigatione del suo Teuere. Roma. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Emory University Readux).

- Figure 13: Cruyl, Lievin. 1664. Eighteen Views of Rome. Collection of The Cleveland Museum of art, Dudley P. Allen Fund 1943.261 (artwork in the public domain, photograph Creative Commons (CC0 1.0) by The Cleveland Museum of art online).

- Figure 14: Falda, Giovanni Battista. 1667. Recentis Romae ichnographia et hypsographia sive planta et facies ad magnificentiam qua sub Alexandro VII P.M. urbs ipsa directa exculta et decorata est. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Emory University Readux).

Bibliography

- Alveri, G. 1664. Roma in ogni stato… di Gasparo Alveri: V. Mascardi.

- Ashby, Thomas, and S. Rowland Pierce. 1924. “The Piazza Del Popolo: Rome. Its History and Development.” The Town Planning Review 11 (2):75-96.

- Carnevali, Gilda, and Gloria Cirocchi. 2004. Egitto a Roma: obelischi: libri e stampe dal fondo antico della Biblioteca : catalogo della mostra. Roma: Camera dei deputati.

- Cipriani, Giovanni Battista. 1823. Su i dodici obelischi egizi che adornano la città di Roma. Roma: Presso A. Ceracchi.

- Ciucci, Giorgio. 1974. La Piazza del Popolo: storia, architettura, urbanistica, Nodi urbani. Roma: Officina.

- Eimer, Gerhard. 1970. La fabbrica di S. Agnese in Navona. Romische Architekten, Bauherren und Handwerker im Zeitalter des Nepotismus. Vol. II. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Falda, Giovanni Battista. 1667. Recentis Romae ichnographia et hypsographia sive planta et facies ad magnificentiam qua sub Alexandro VII P.M. urbs ipsa directa exculta et decorata est.

- Falda, Giovanni Battista, and Giovanni Giacomo De Rossi. 1665-1669. Il nuovo teatro delle fabbriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna. 3 vols. [Roma]: Giovanni Giacomo De Rossi.

- Falda, Giovanni Battista, and Giovanni Giacomo De Rossi. 1676. Nuova pianta et alzata della citta di Roma con tutte le strade piazze et edificii de tempii : palazzi, giardini et altre fabbriche antiche e moderne come si trovano al presente nel pontificato di N.S. papa Innocentio XI. con le loro dichiarationi nomi et indice copiosissimo. Roma: de Rubeis.

- Falda, Giovanni Battista, Giovanni Francesco Venturini, and Giovanni Giacomo De Rossi. 1691. Le fontane di Roma nelle piazze e luoghi publici della città : con li loro prospetti, come sono al presente. In Roma: [Gio. Giacomo De Rossi dalle sue stampe …

- Golzio, Vincenzo. 1941. “Le Chiese di S. Maria di Montesanto e di S. Maria dei Miracoli a Piazza del Popolo in Roma.” Archivi archivi d’Italia e rassegna internazionale degli archivi. Serie II, VIII:122-47.

- Hager, Hellmut. 1967/1968. “Zur Planungs- und Baugeschichte der Zwillingskirchen auf der Piazza del Popolo: S. Maria di Monte Santo und S. Maria dei Miracoli in Rom.” Römisches Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte 11:191-307.

Hempel, Eberhard. 1919. “Carlo Rainaldi : ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des romischen Barocks.” - Krautheimer, Richard, and Roger Beauchamp Spencer Jones. 1975. “The diary of Alexander VII: notes on art, artists and buildings.” Romisches Jahrbuch fur Kunstgeschichte 15:199-236.

- Meijer, Cornelis. 1685. L’arte di restituire à Roma la tralasciata nauigatione del suo Teuere: diuisa in tre parti. [Roma]: Nella stamperia della Reuerenda Camera Apostolica.

- Rossi, Giovanni Giacomo de. 1684. Insignium Romae templorum prospectus exteriores interioresque : a celebrioribus architectis inventi : nunc tandem suis cum plantis ac mensuris. [Rome]: Jo[sephus] Jacobo de Rubeis …

- Rossini, Luigi. 1829. Le Porte antiche e moderne del recinto di Roma con le mura, prospetti e piante geometriche disegnate ed incise dall’architetto L. Rossini: Roma.

Leave a Reply