The Colosseum

by Joanna Mundy

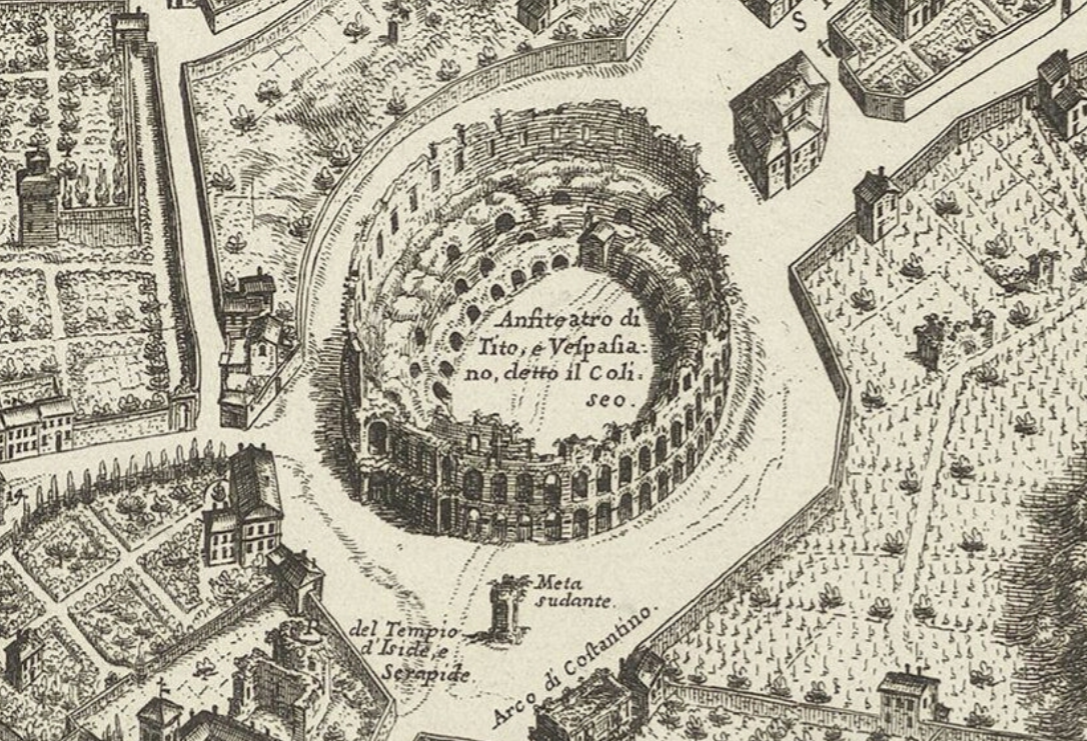

The grand profile of the monumental Colosseum is one of the best known symbols of the city of Rome, and is immediately visible just right of center in Falda’s 1676 Nuova pianta et alzata della citta di Roma (Figure 1). Built over the infamous lake of the Emperor Nero’s Domus Aurea, the Colosseum was constructed and presented for the use of the public of Rome in ancient times, accommodating spectacles of grand scale.[1] Originally called the Amphitheater, or Flavian Amphitheater, for the Flavian emperors who constructed it, it acquired the name of Colosseo by the eighth century from the nearby Colossus of Nero, an ostentatious statue of the emperor.[2]

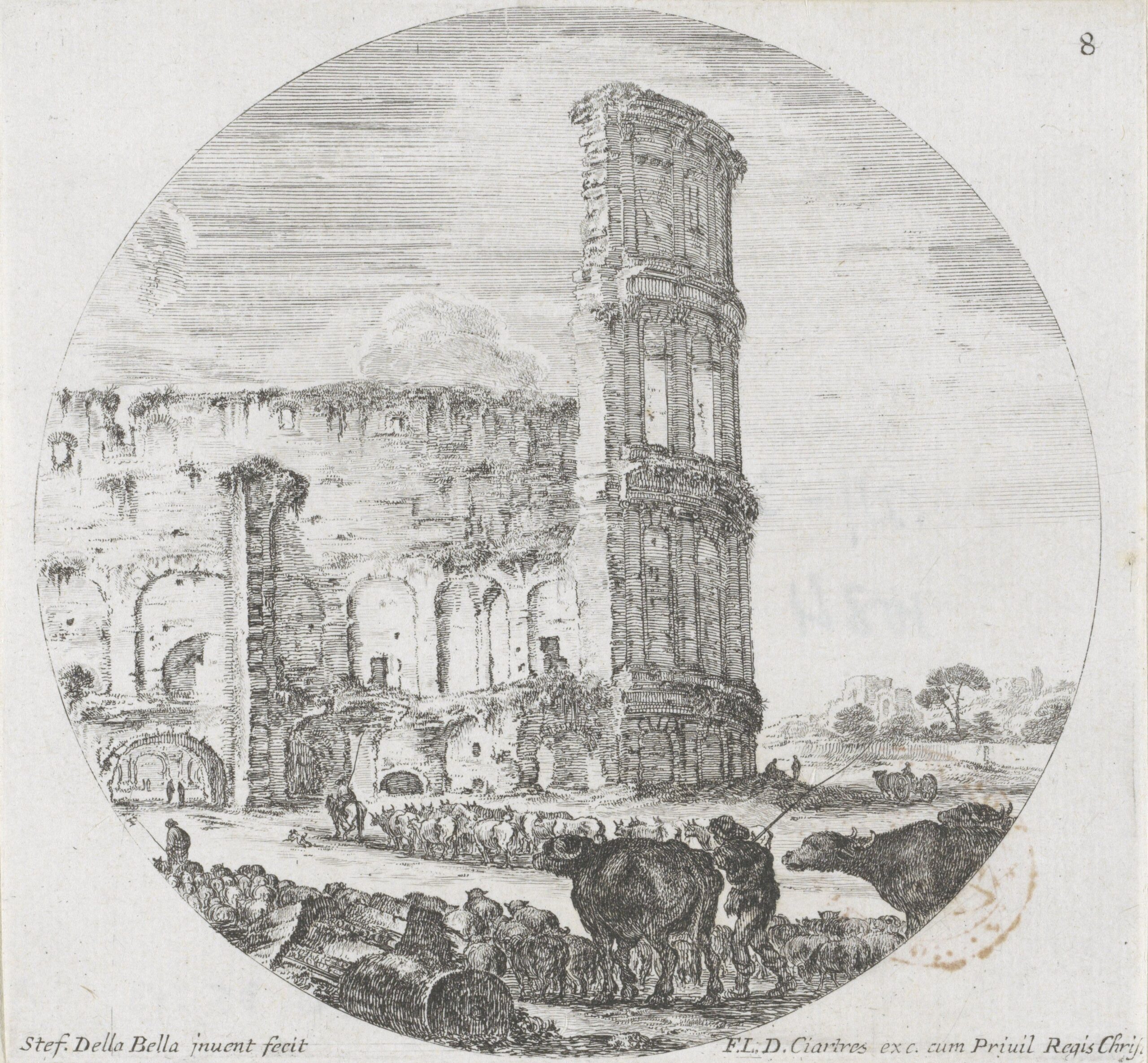

In the medieval and early modern periods, this monumental structure was, instead, a vestige of ancient Rome, providing some protection from sun and weather for livestock and shepherds in the pastoral landscape. An early seventeenth-century print by Stefano della Bella in the Rijksmuseum clearly depicts this period, with shepherds, cows, and sheep around the Colosseum (Figure 2).

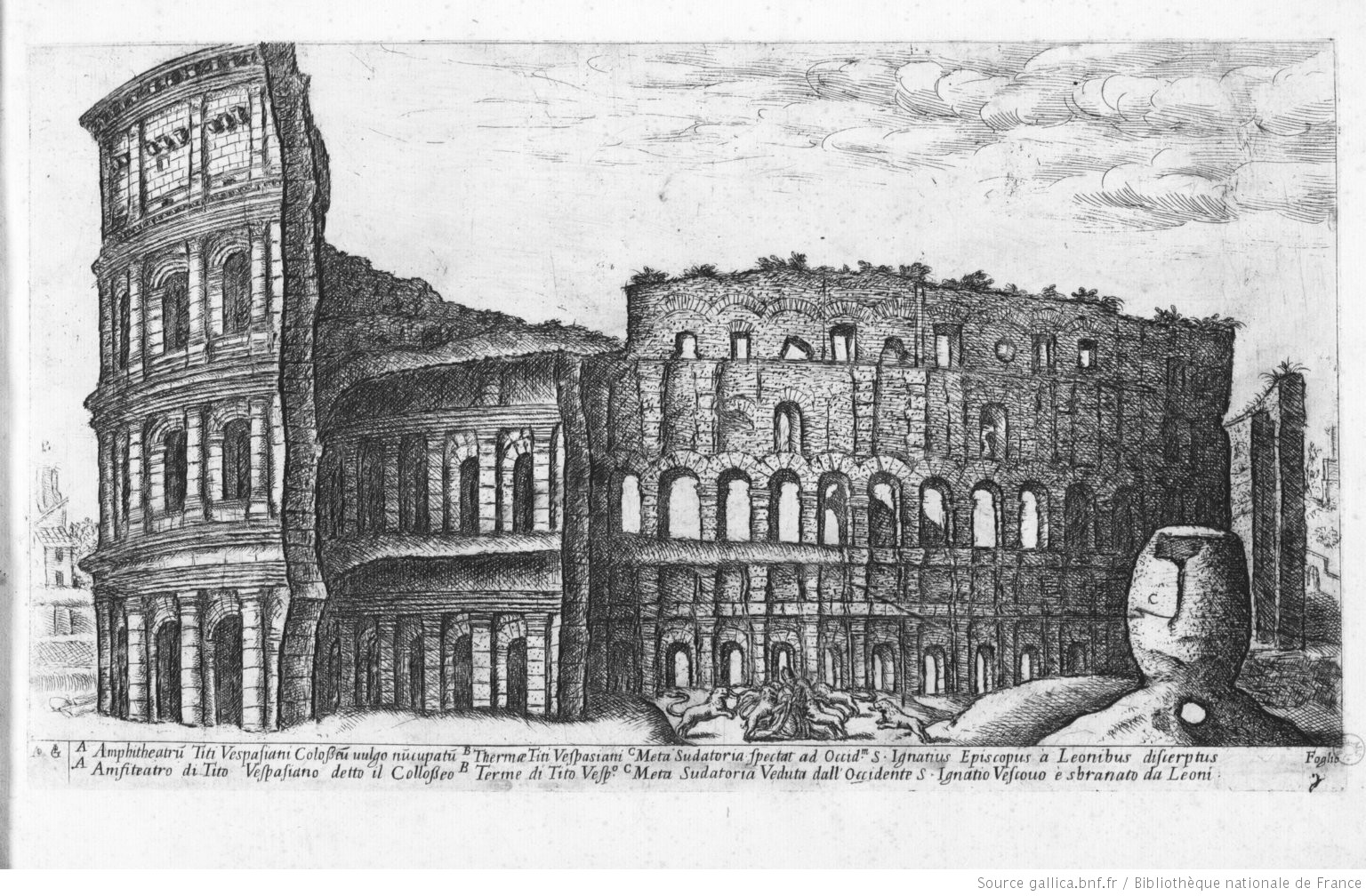

Eligio “Alò” Giovannoli underlines the symbolism of the ancient structure in 1616 in his Vedute degli antichi vestigi di Roma (Figure 3). Giovannoli evokes the Christian history of the site when he depicts lions mauling Saint Ignatius in the foreground. This martyrdom in the Colosseum from the second century CE ties the building to both Rome and the church.[3]

-

Figure 3: A. Giovannoli, Amphitheatru Titi Vespasiani Colosseu uulgo nucupatu…, 1616. -

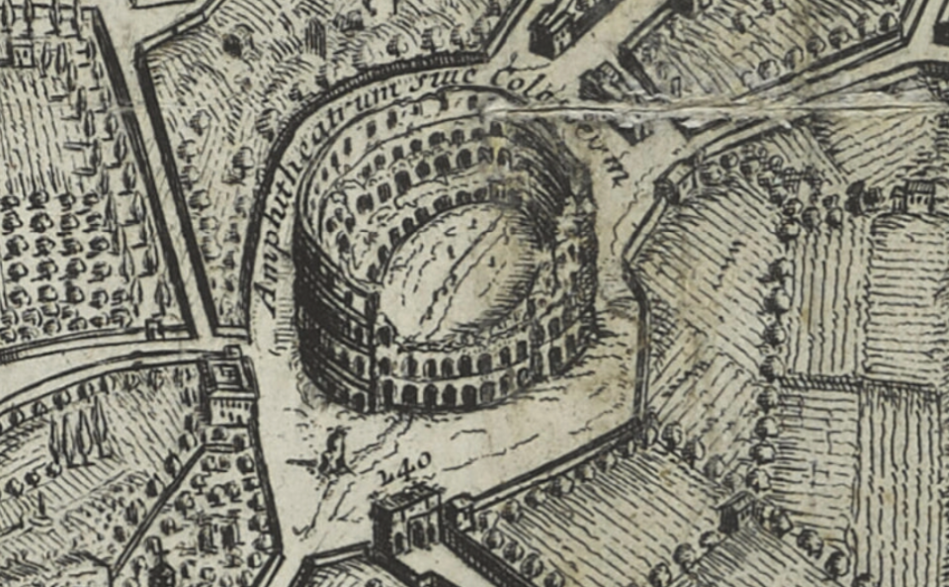

Figure 4: Detail of the Colosseum from G.B. Falda, Recentis Romae ichnographia et hypsographia sive planta et facies…, 1667.

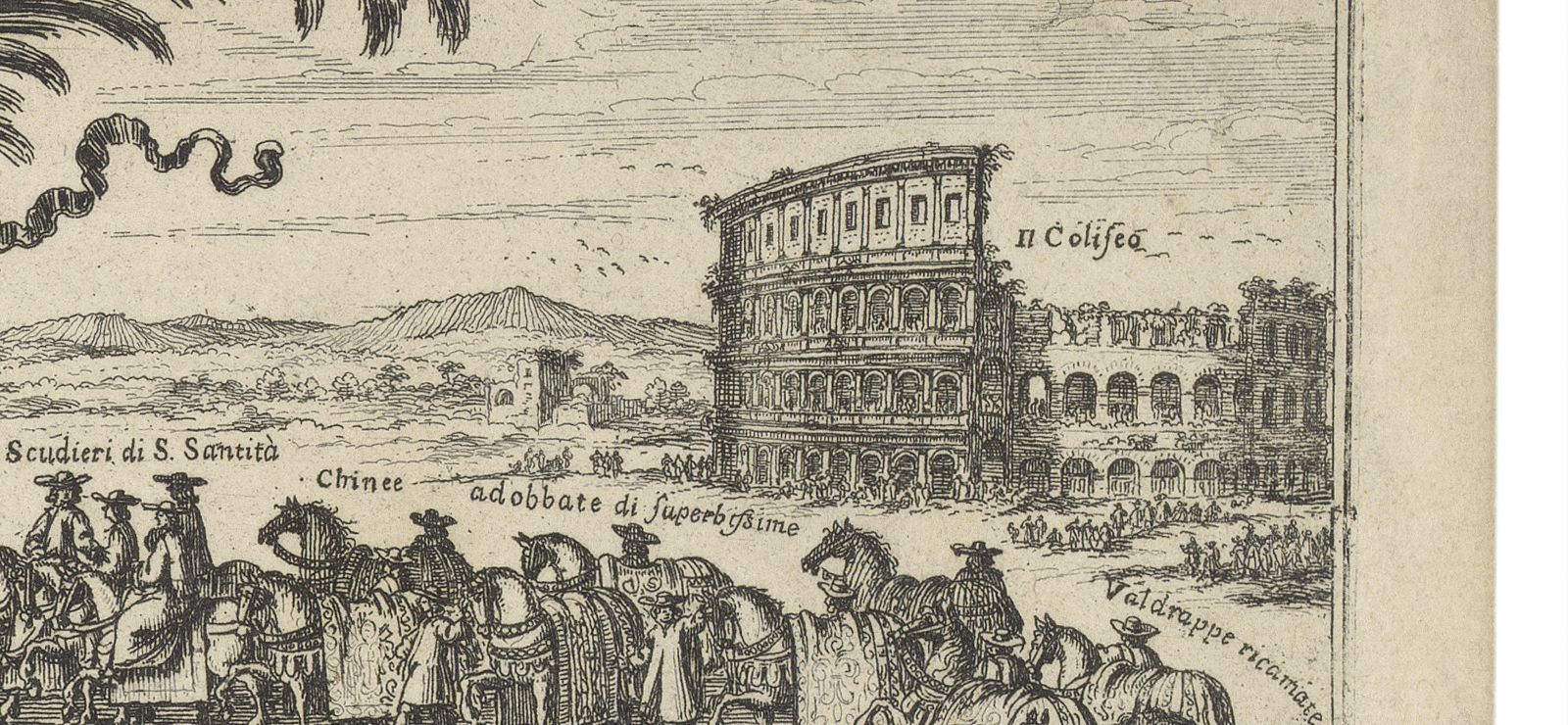

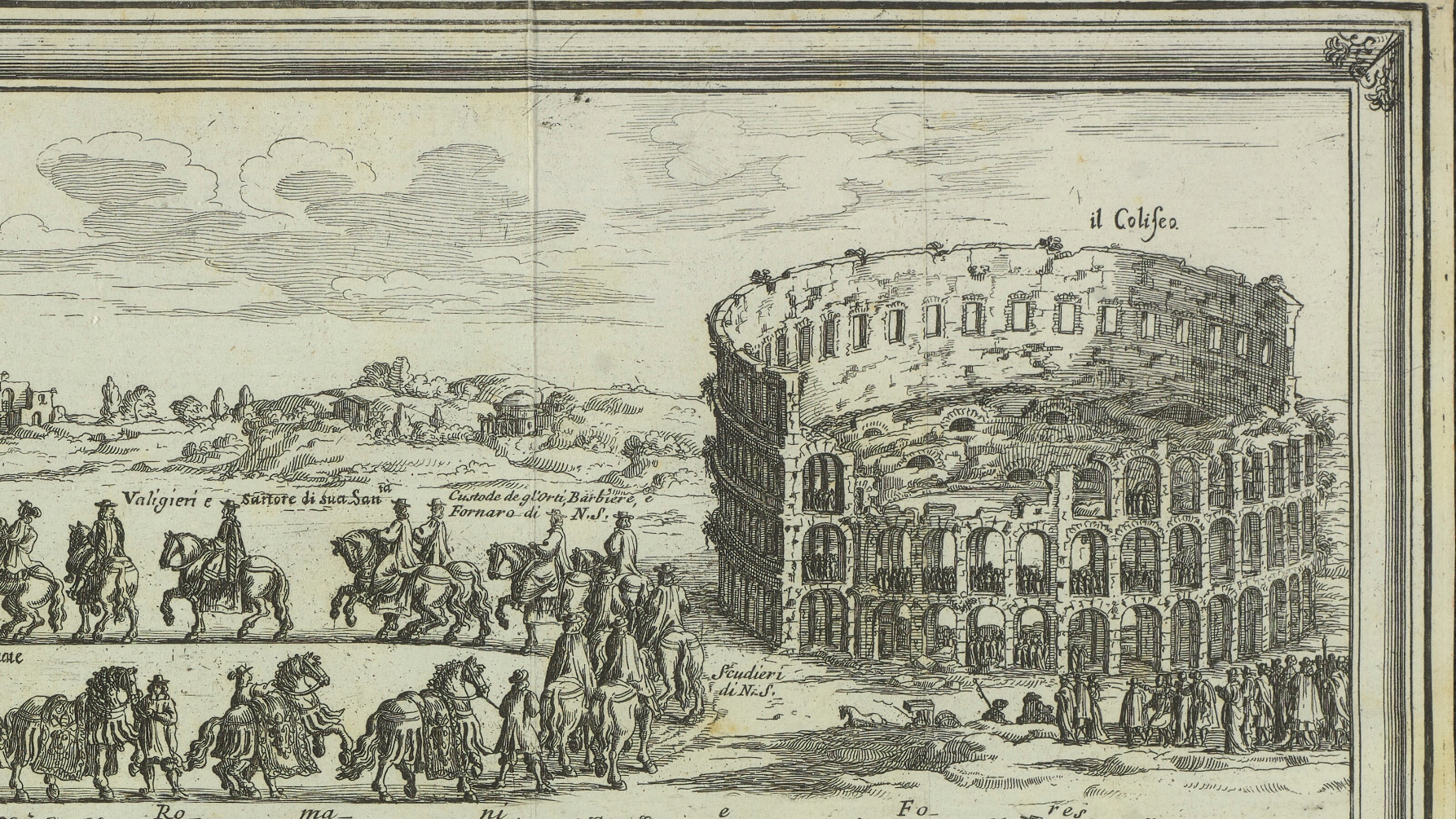

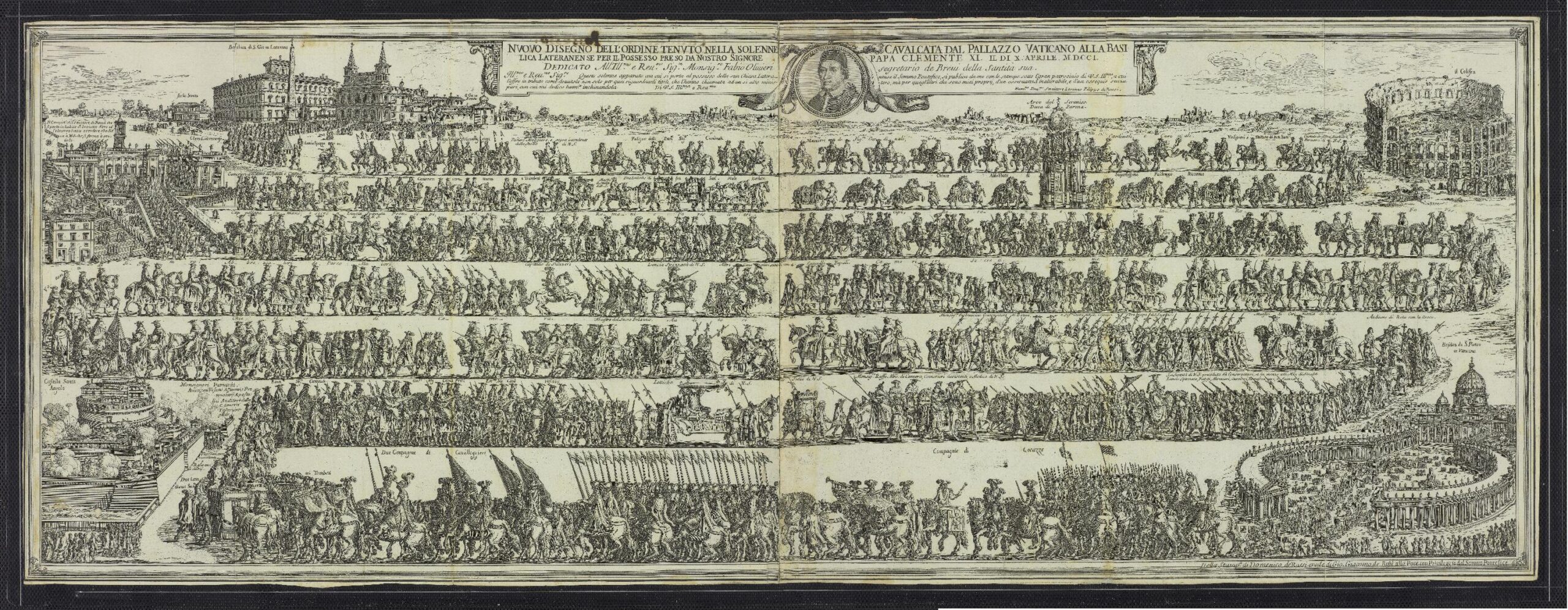

For the digital reconstruction of the Colosseum, we took an experimental approach. While the Colosseum is an impressive and prominent structure in the architectural history of Rome, as well as a symbol of the city, it’s role as a key historical site was at odds with the cultivated image of modern Rome that Falda was depicting for the papacy. While grand depictions of antiquity were popular for printmakers in the sixteenth century, Falda highlights a new subject in the seventeenth century: a modern Rome in which the papacy was engaged in urban renewal.[4] Because of this, Falda’s vedute concentrate on the recent Baroque constructions in the city: palazzi, chiese, and piazze. The Colosseum, by contrast, is depicted only in his maps (Figures 1 and 4) and as a point of reference for the cavalcata or procession traversing the city in his papal possesso prints (Figures 5 and 6). A small portion of the structure can also be seen in Falda’s view of Santa Francesca Romana (Figure 7).

-

Figure 5 (Detail): Detail of the Colosseum from G.B. Falda, Nuouo disegno dell’ ordine tenuto nella solenne caualcata…, 1676. -

Figure 5: G.B. Falda, Nuouo disegno dell’ ordine tenuto nella solenne caualcata…, 1676.

-

Figure 6 (Detail): Detail of the Colosseum from G.B. Falda, Solenne cavalcata dal Palazzo Vaticano alla Basilica Lateranense per il possesso di Papa Clemente XI., 1701. -

Figure 6: G.B. Falda, Solenne cavalcata dal Palazzo Vaticano alla Basilica Lateranense per il possesso di Papa Clemente XI., 1701.

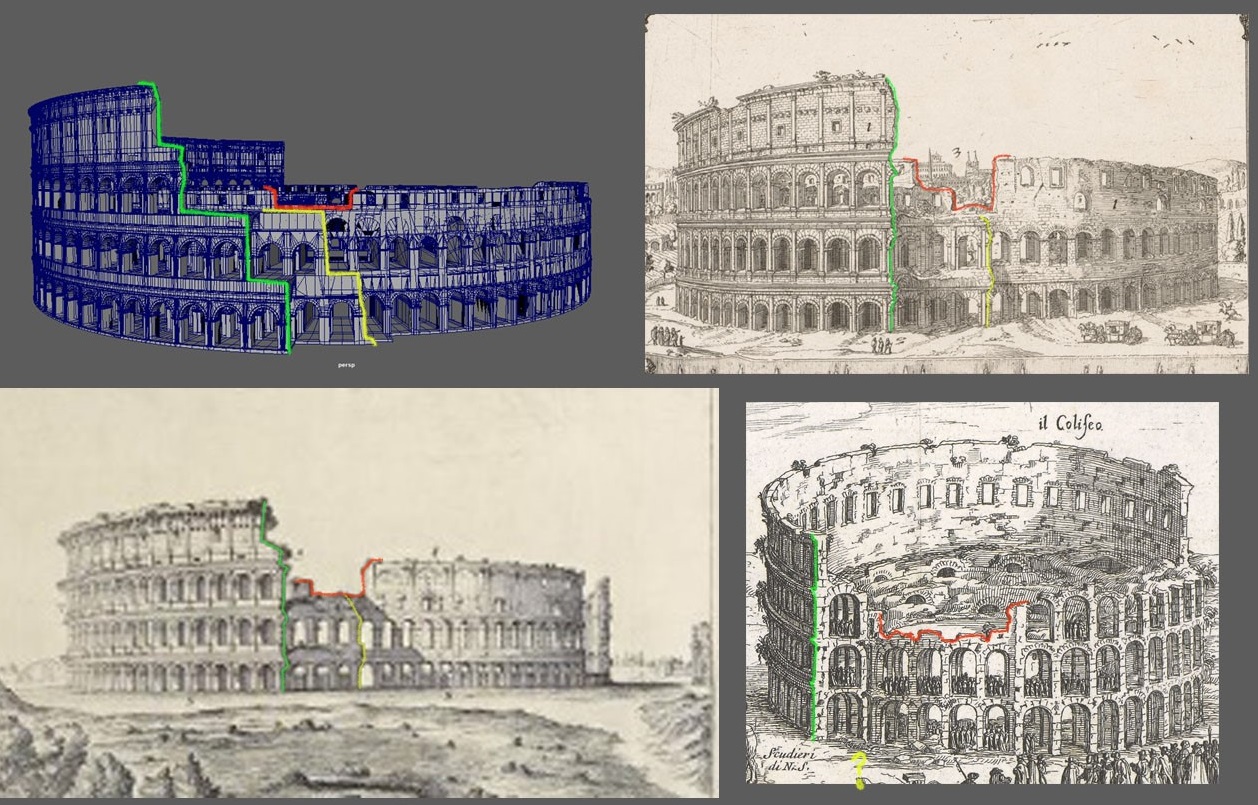

As this major monument is very complex in design, and was represented with less detail by Falda, we took the opportunity to test a new modelling method with an eye for effectiveness and expediency in creating large structures. We purchased a 3D model of the Colosseum as it stands today, called “Roman Colosseum Ruins” from Turbosquid by artist QuickEasy3d with a royalty-free license, allowing us to edit and use the revised model in our build.[5] Our modeler had to make considerable adjustments

to the purchased model to remove the changes that the monument has sustained between 1676 and today. The Colosseum was witness to various destructions and restorations over the course of this period. Individual sections of brick from the circuit walls have fallen, requiring us to compare the structure of the arches as rendered in the model to what remained on the exterior of the Colosseum in the seventeenth century (Figure 8). Additionally, restoration efforts began at the beginning of the 1800s, with Pope Pius VII commissioning work by Giuseppe Camporese, undertaken in 1808, to create the first spur, or angled brick support of the wall. Valadier undertook the second spur between 1822 and 1826. Restoration work on the Colosseum continued in the nineteenth century with efforts in 1828, 1845, and 1852 under three different popes.[6]

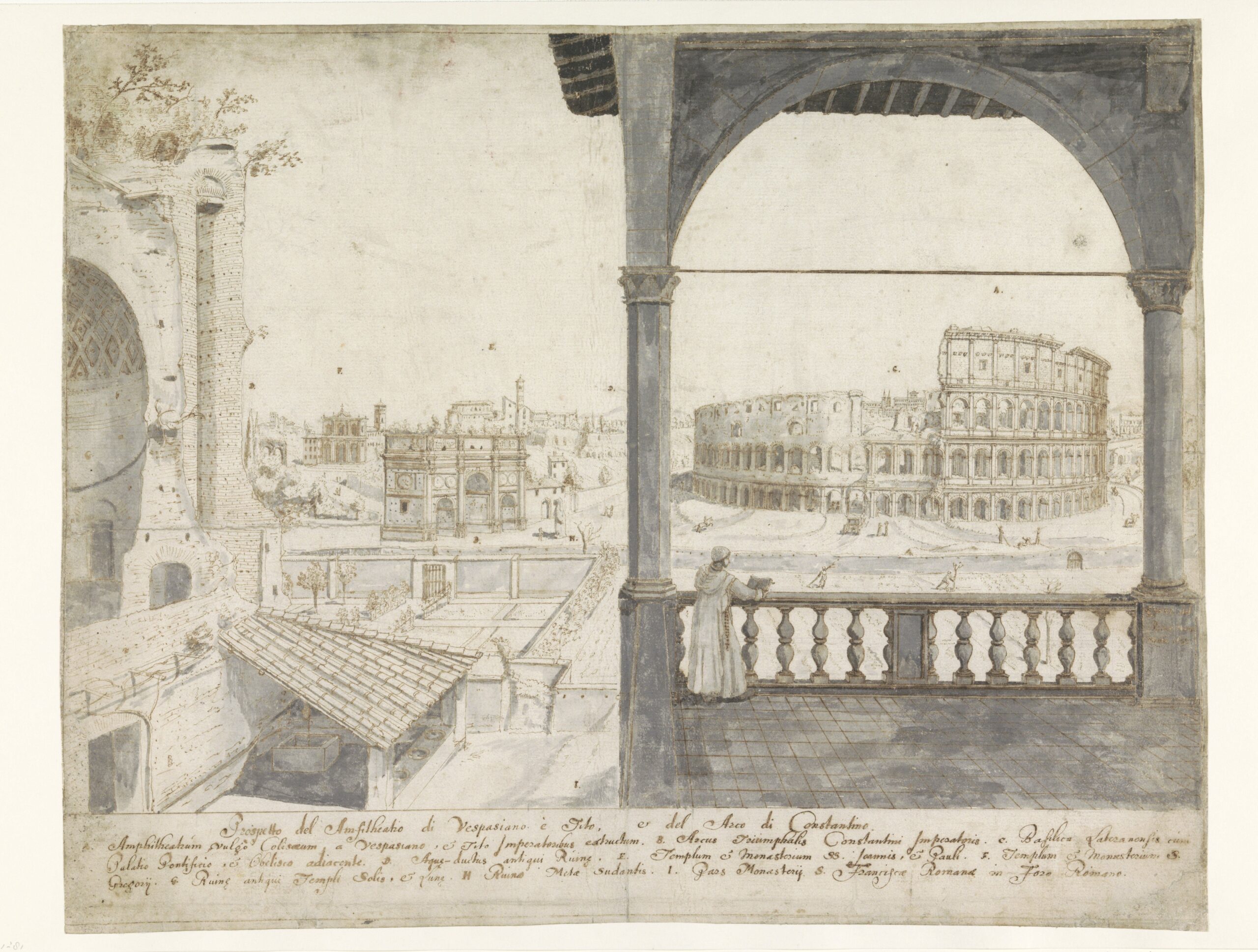

A few key sources provided the evidence from the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries for the deconstruction and reconstruction of the early modern Colosseum. These include the pen and ink drawing and print, Il Colosseo e l’Arco di Costantino, by Lievin Cruyl (Figures 9 and 10). The clear view of the Colosseum presented by Cruyl includes the Temple of Venus and Roma, the Arch of Constantine, and the Colosseum. The monument is depicted from the perspective of a balcony in the monastery associated with Santa Francesca Romana. Additionally, Falda’s Solenne cavalcata dal Palazzo Vaticano alla Basilica Lateranense per il possesso di Papa Clemente XI (Figure 6) provides a point of comparison, showing a more comprehensible perspective on the monument than in his maps of Rome, which depict the Colosseum from above.

-

Figure 9: L. Cruyl, Prospetto del Amfitheatro di Vespano e Tito, e del Arco di Constantino, 1664. -

Figure 10: L. Cruyl, Il Colosseo e l’Arco di Costantino., 1666.

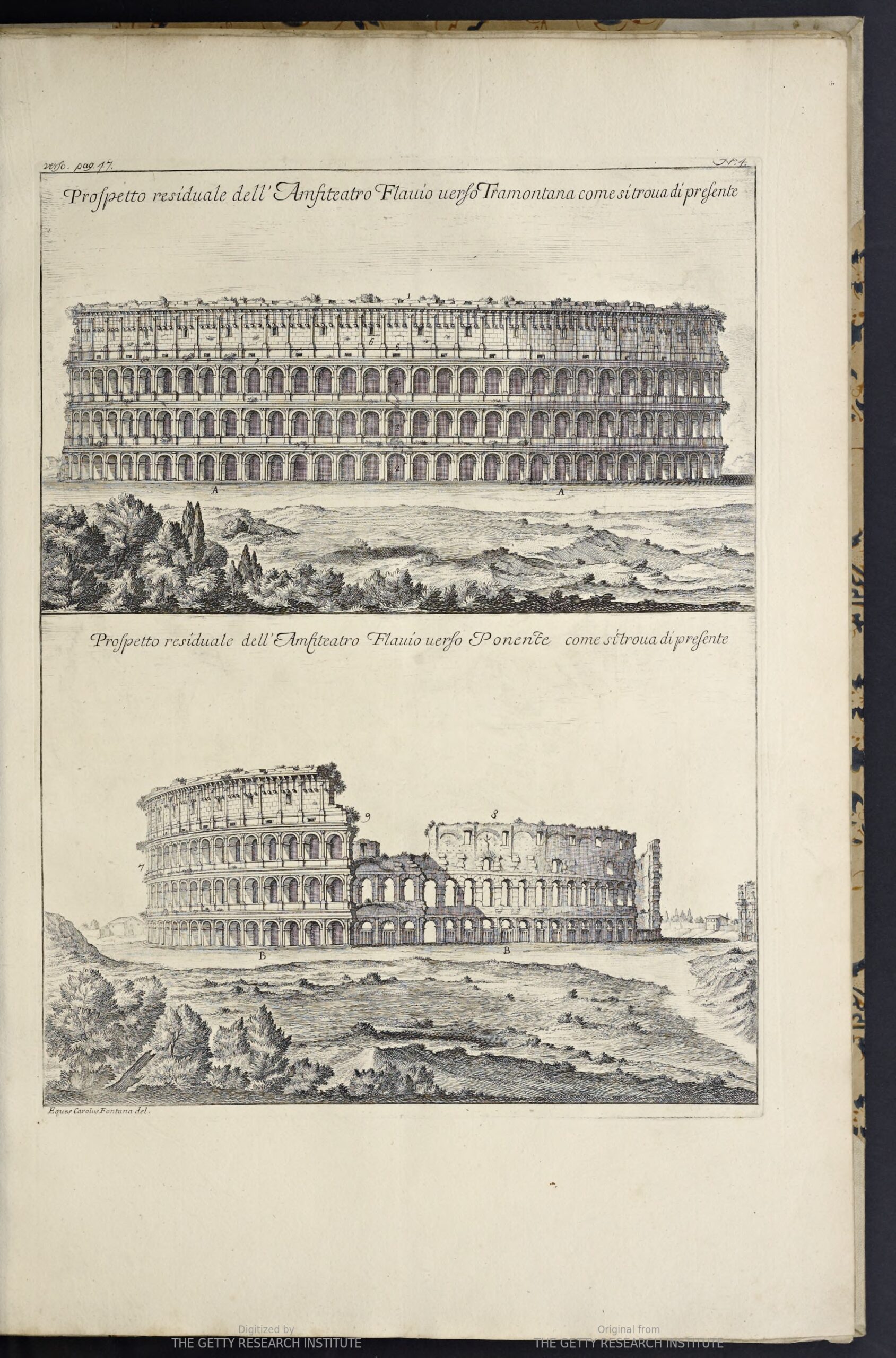

A third useful illustration for comparison was the Prospetto residuale dell’Amfiteatro Flavio verso Ponente come si trova di presente by Carlo Fontana (Figure 11), an extremely detailed print from his 1725 book on the subject, L’anfiteatro Flavio, descritto e delineato dal cavaliere Carlo Fontana. In addition to these central sources, another illustration of the scene, a probable miniature drawing on vellum by Cruyl, provides additional detail.[7] After Dr. Sarah McPhee and modeler Nicole Costello Matthews examined and compared the purchased model of the Colosseum, as it stands today, and available early modern sources, a combination of the silhouette depicted by Carlo Fontana and that by Lievin Cruyl were chosen for the reconstruction. Costello Matthews then removed the restorations of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries on the 3D model, eliminating the modern brick added for stability and restoring pieces that had fallen after 1676 but before the restorations of the nineteenth century. She also remapped the model in order to texture the surface with color, detail, and shading to match the prints of Falda, as in the rest of Envisioning Baroque Rome.

-

Figure 11: C. Fontana, “Prospetto residuale dell’Amfiteatro Flavio verso Ponente come si trova di presente,” L’anfiteatro Flavio, 1725. -

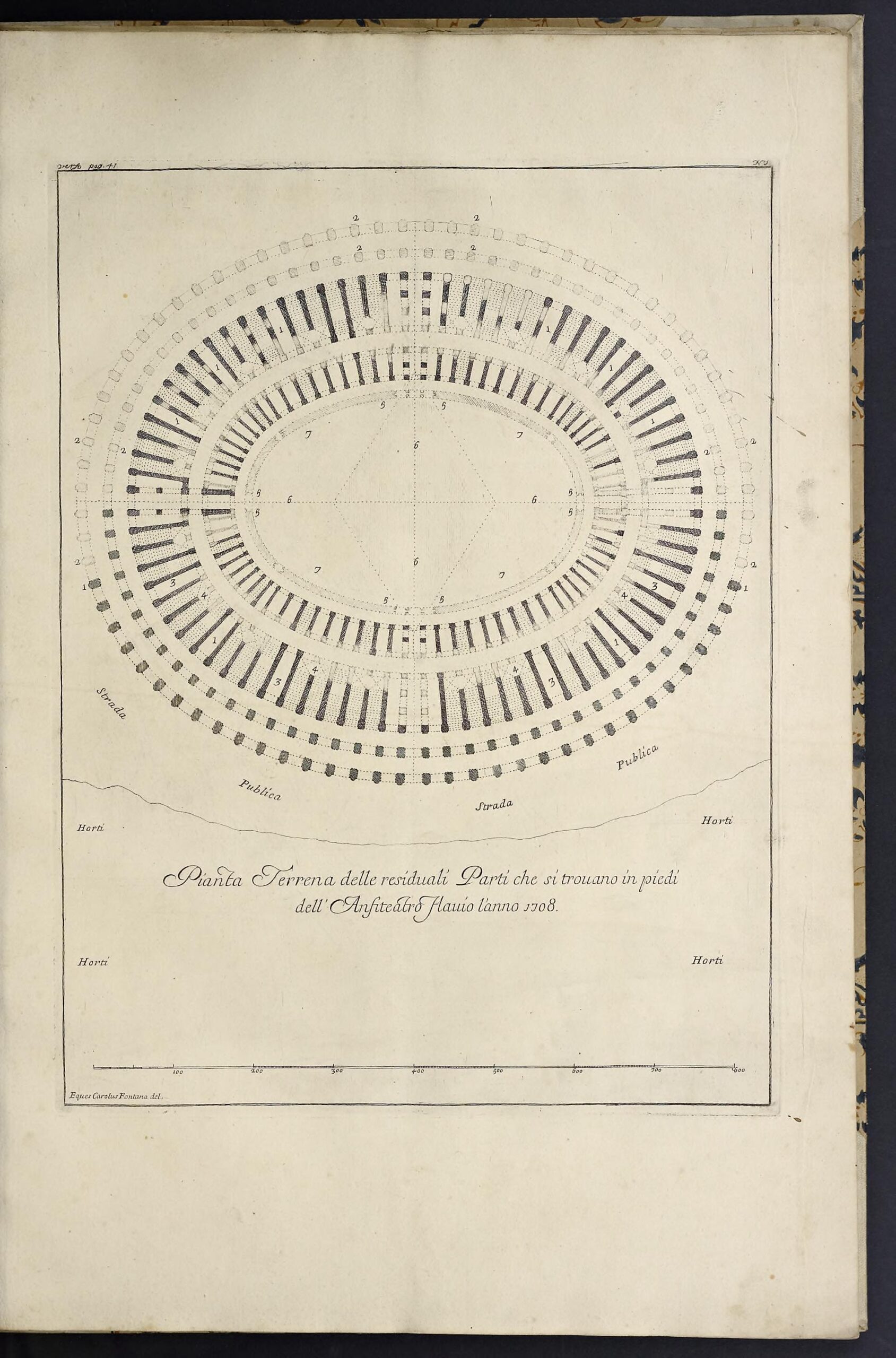

Figure 12: C. Fontana, “Pianta Terrena delle residuali Parti che si trovano in piedi dell’Anfiteatro Flavio l’anno 1708,” L’anfiteatro Flavio 1725.

Costello Matthews also measured and assessed the Turbosquid model of the Colosseum and compared it to other records of the monument’s plan. The Pianta Terrena delle residuali Parti che si trovano in piedi dell’Anfiteatro Flavio l’anno 1708 by Carlo Fontana from the same book provided an historical source (Figure 12). A “Plan of the Colosseum” by Tom Cross provided a modern, highly detailed point of comparison.[8] Finally, we placed and scaled the edited model of the Colosseum on the plan of the Nuova pianta di Roma by Giambattista Nolli (Figure 13). It is important to note that the Colosseum in the Envisioning Baroque Rome world is intentionally partially buried under the ground, as the level had risen considerably since the first century, due to floods. Excavations of the monument did not begin until the early nineteenth century under Carlo Fea.[9]

This research resulted in our reconstructed seventeenth century Colosseum (Figure 14). We learned a great deal from the experimental approach adopted for the Colosseum. While we thought that purchasing the model did expedite the time spent modeling, the additional stage of remapping the textures and thoughtfully deconstructing and reconstructing portions of the model to reflect the seventeenth-century state of the Colosseum took extensive time and research. While happy with the result, it was not a clearly faster approach.

[1] Champlin 2005, 208.

[2] Pietrangeli 1983, 19.

[3] Pirozzolo 2023, https://www.arborsapientiae.com/notizia/913/roma-antica-nelle-incisioni-di-eligio-giovannoli.html.

[4] Blunt notes that the Palazzo Venezia does not have any Baroque features, other than the fountain by Benedict XIII, erected in 1730. Blunt 1982, 199; De Rossi, and Falda c. 1670.

[5] We do not re-share the original or edited model, it is incorporated in the build. QuickEasy3d 2010, https://www.turbosquid.com/FullPreview/545131.

[6] Pietrangeli 1983, 22.

[7] For this image, see Cruyl 1670, https://www.museodiroma.it/en/collezioni/percorsi_per_temi/grafica/veduta_del_colosseo_con_l_arco_di_costantino.

[8] Cross, Tom. “Plan of the Colosseum,” in Hopkins and Beard 2012, fig. 1.

[9] Pietrangeli 1983, 22; Museo di Roma – Gabinetto delle Stampe https://simartweb.comune.roma.it/dettaglio-bene/-663898297.

Figures:

- Figure 1: “Detail of the Colosseum” from Giovanni Battista Falda. 1676. Nuova pianta et alzata della citta’ di Roma con tutte le strade, piazza et edificii de tempi, palazzi, giardini et altre fabbriche antiche e moderne come si trovano al presente nel pontificato do N.S. Papa Innocentio XI con le loro dichiarationi nomi et indice copiosissimo. Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Object number: RP-P-OB-207.658 (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by the Rijksmuseum, https://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.587478).

- Figure 2: Stefano della Bella. 1646. “Herds of cows and sheep in front of the Colosseum,” in Paysages et ruines de Rome. Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Object Number RP-P-OB-35.113 (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided public domain by the Rijksmuseum https://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.77405

- Figure 3: Alo Giovannoli. 1616. “Amphitheatru Titi Vespasiani Colosseu uulgo nucupatu…” In Vedute degli antichi vestigi di Roma. Collection of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Arsenal, EST-1303 (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided public domain by the Bibliothèque nationale de France https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k841373b/f2.item).

- Figure 4: Giovanni Battista Falda. 1667. Recentis Romae ichnographia et hypsographia sive planta et facies ad magnificentiam qva svb Alexandro VII P.M. vrbs ipsa directa excvlta et decorata est. Rome: G.G. de Rossi. Collection of Emory University Libraries FOLIO 2012 43 (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided public domain by Emory Readux).

- Figure 5: Giovanni Battista Falda. 1676. Nuouo disegno dell’ ordine tenuto nella solenne caualcata dal Palazzo Vaticano alla Basilica Lateranense per il possesso preso da N.S. Papa Innocentio XI il di VII Nouembre MDCLXXVI. Collection of Folger Shakespeare Library Online (artwork in the public domain, photograph CC BY-SA 4.0 from Folger Shakespeare Library https://digitalcollections.folger.edu/img36441).

- Figure 6: Giovanni Battista Falda. 1701. Solenne cavalcata dal Palazzo Vaticano alla Basilica Lateranense per il possesso di Papa Clemente XI. Roma: Nella stampa di Domenico de Rossi erede di Gio. Giacomo de Rossi alla Pace con Priuileggio del Sommo Pontefice. Collection of the Emory University Libraries ELE FOLIO 2013 185 (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided public domain by Emory Readux).

- Figure 7: Giovanni Battista Falda. 1667-1669. “Chiesa Sotto il Titolo di S. Maria Nvova et S. Francesca Romana in Campo Vaccino,” from Il nuovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna, vol. 3, print 9. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided public domain by Emory Readux).

- Figure 8: Clockwise comparison of the original wireframe of the Turbosquid model “Roman Colosseum Ruins” by QuickEasy3d with details from Figures 10, 6, and 11.

- Figure 9: Lievin Cruyl. 1664. Gezicht te Rome op het Colosseum en de boog van Constantijn / Prospetto del Amfitheatro di Vespano e Tito, e del Arco di Constantino. Collection of the Rijksmuseum Object Number RP-T-1949-557 (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided public domain by the Rijksmuseum https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/RP-T-1949-557).

- Figure 10: Lievin Cruyl. 1666. “Il Colosseo e l’Arco di Costantino” from Prospectus Locurum Urbis Romae Insign[ium]. Collection of The Cleveland Museum of Art, Andrew R. and Martha Holden Jennings Fund 1991.64.10 (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided CC0 by Archive.org and The Cleveland Museum of Art https://archive.org/details/clevelandart-1991.64.10-il-colosseo-e-l-arco).

- Figure 11: Carlo Fontana. 1725. “Prospetto residuale dell’Amfiteatro Flavio verso Ponente come si trova di presente,” from L’anfiteatro Flavio, descritto e delineato dal cavaliere Carlo Fontana. Nell’ Haia, Appresso I. Vaillant. Collection of the Getty Research Institute Call number 9926625600001551 (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by the Getty Research Institute through archive.org https://archive.org/details/gri_33125012907867/page/n59/mode/2up).

- Figure 12: Carlo Fontana. 1725. “Pianta Terrena delle residuali Parti che si trovano in piedi dell’Anfiteatro Flavio l’anno 1708,” from L’anfiteatro Flavio, descritto e delineato dal cavaliere Carlo Fontana. Nell’ Haia, Appresso I. Vaillant. Collection of the Getty Research Institute Call number 9926625600001551 (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by the Getty Research Institute through archive.org https://archive.org/details/gri_33125012907867/page/40/mode/2up).

- Figure 13: “Detail of the Colosseum” from Giambattista Nolli. 1748. Nuova pianta di Roma. Collection of the Getty Research Institute, Call number 9923924260001551 (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by the Getty Research Institute through archive.org https://archive.org/details/gri_33125008447415).

- Figure 14: Screenshot of the Colosseum from Envisioning Baroque Rome. (artwork copyright Sarah McPhee, photograph provided by Envisioning Baroque Rome).

Bibliography

- Champlin, Edward. 2005. Nero. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Cruyl, Lievin. 1670. Veduta del Colosseo con l’Arco di Costantino. Collection of Museo di Roma website. https://www.museodiroma.it/en/collezioni/percorsi_per_temi/grafica/veduta_del_colosseo_con_l_arco_di_costantino.

- Hopkins, Keith, and Mary Beard. 2012. The Colosseum. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Krautheimer, Richard. 1985. The Rome of Alexander VII, 1655-1667. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Museo di Roma – Gabinetto delle Stampe. (Accessed June 23, 2023). “L’abate Carlo Fea e gli scavi nel Colosseo: 1813 (circa).” SIMARTweb: Roma Culture. https://simartweb.comune.roma.it/dettaglio-bene/-663898297.

- Pietrangeli, Carlo. 1983. Rione XIX – Celio: Parte I, Guide Rionali di Roma. Roma: Fratelli Palombi Editori.

- Pirozzolo, Diego. 2023, (Accessed June 21, 2023). “Arbor Sapientiae: Editore & Distributore Specializzato in Scienze Umanistiche.” Roma antica nelle incisioni di Eligio Giovannoli. https://www.arborsapientiae.com/notizia/913/roma-antica-nelle-incisioni-di-eligio-giovannoli.html.

- QuickEasy3d. 2010. Roman Colosseum Ruins. Turbosquid. Collection of TurboSquid Ancient Ruins. TurboSquid 3D Model License, ID 545131. https://www.turbosquid.com/FullPreview/545131.

- Speed, Bonnie. 2013. Preface. In Antichità, Teatro, Magnificenza: Renaissance & Baroque Images of Rome. Atlanta: Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University.

Leave a Reply