The Piazza della Rotonda and Piazza della Minerva

by Joanna Mundy

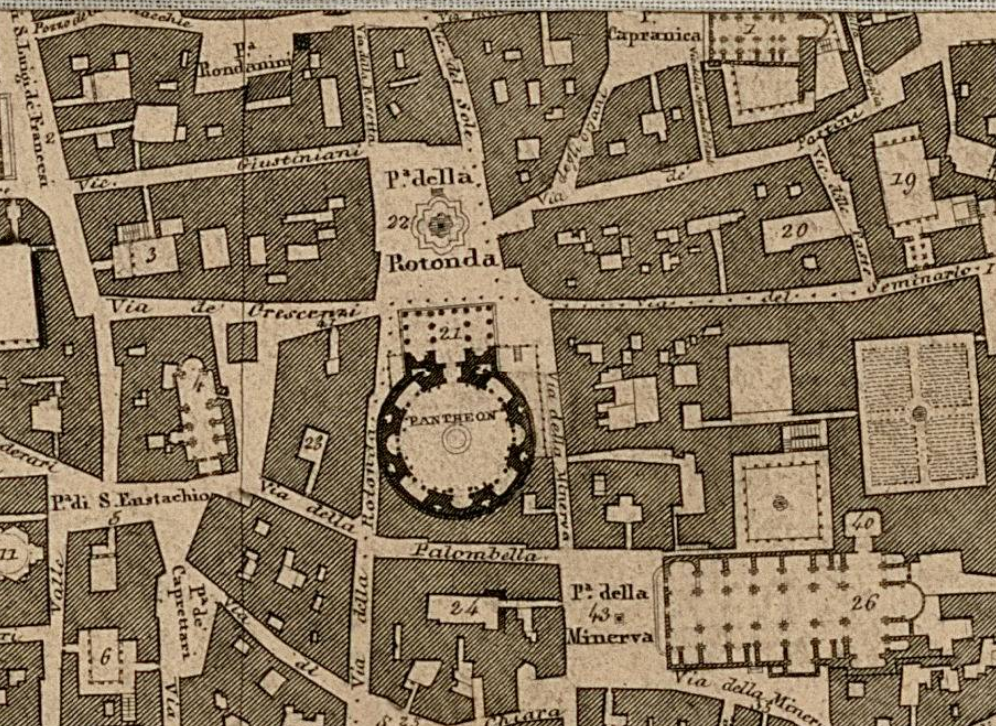

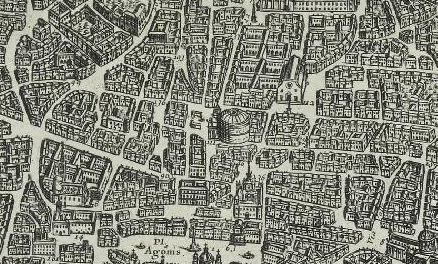

The Pantheon and Piazza della Rotonda have long been an important hub in the Campus Martius in central Rome. As one of the most impressive remaining ancient Roman buildings, located within an urban space at the heart of north-south traffic in trade and daily life, the Pantheon could not escape the attention of Alexander VII Chigi (r. 1655-67).[1] In order to reconstruct this space for Envisioning Baroque Rome, we focused on prints of the piazza and area by Giovanni Battista Falda. The 1676 Nuova pianta et alzata della citta’ di Roma of Falda provided a bird’s eye view of the piazza and surrounding streets (fig. 1), and the 1748 Nuova Pianta di Roma by Giambattista Nolli provided a measured plan of the same area (fig. 2).

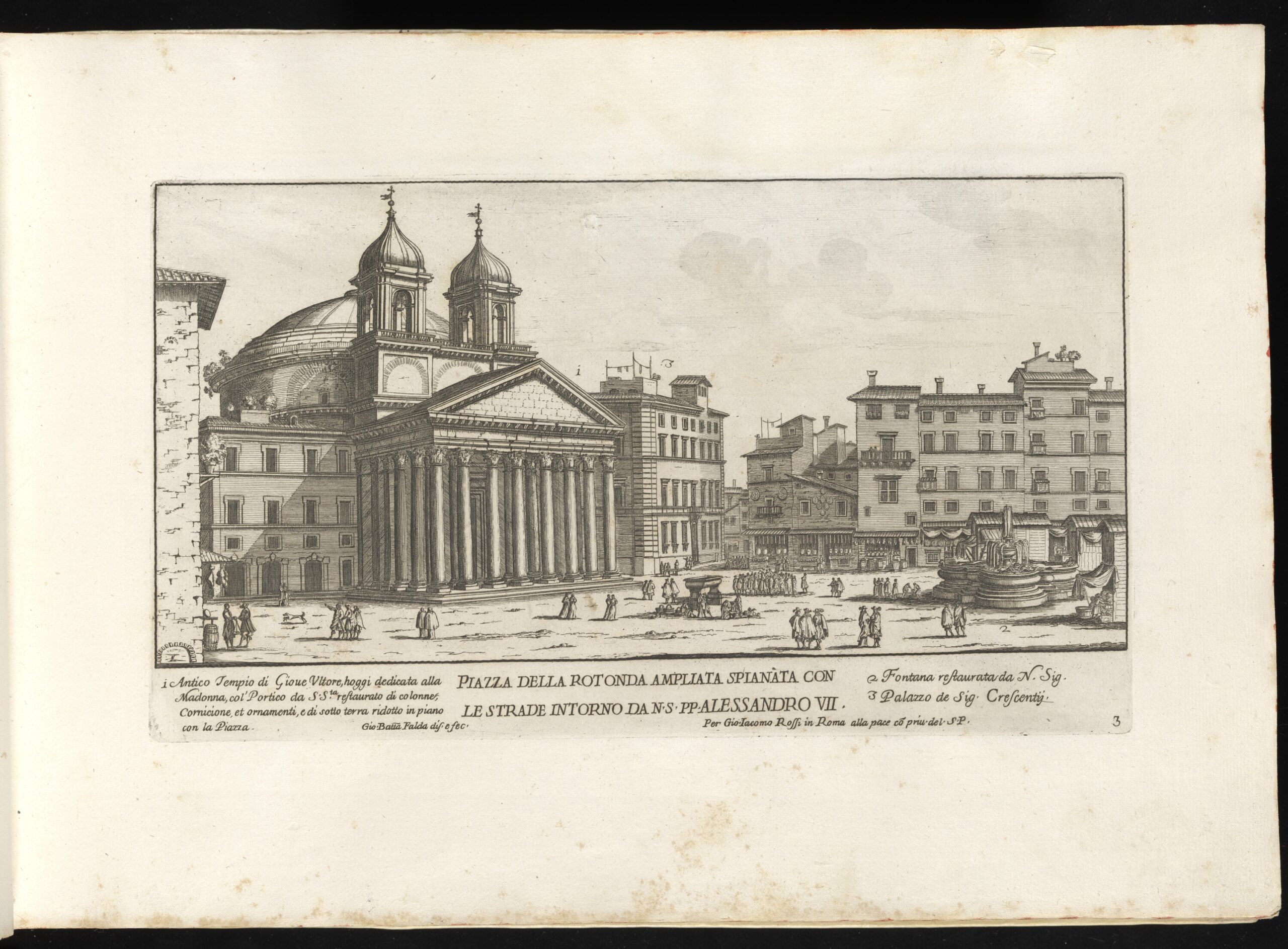

The primary views that show the Piazza della Rotonda include the print Fontana nella Piazza della Rotonda from Le fontane di Roma nelle piazze e lvoghi pvblici della città, con li loro prospetti, come sono al presente (fig. 3)[2], which shows a view of the fountain from the perspective of the Pantheon. Two other prints of the piazza, facing the Pantheon, are found in Il nvovo teatro delle fabriche, et

edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna by Falda (fig. 4 and 5). Here, two prospects of the Pantheon are provided by the print Piazza Della Rotonda Ampiata Da N.S. Papa Alesandro VII, print 31 from vol. 1 and the later print from vol. 2, print 3, Piazza della Rotonda Ampliata Spianata Con Le Strade Intorno Da N.S. PP. Alessandro VII.

-

Figure 4: G.B. Falda, Piazza della Rotonda ampiata da N.S. Papa Alesandro VII, 1665. -

Figure 5: G.B. Falda, Piazza della Rotonda ampliata spianata con le strade intorno da N.S. PP. Alessandro VII, 1665-67.

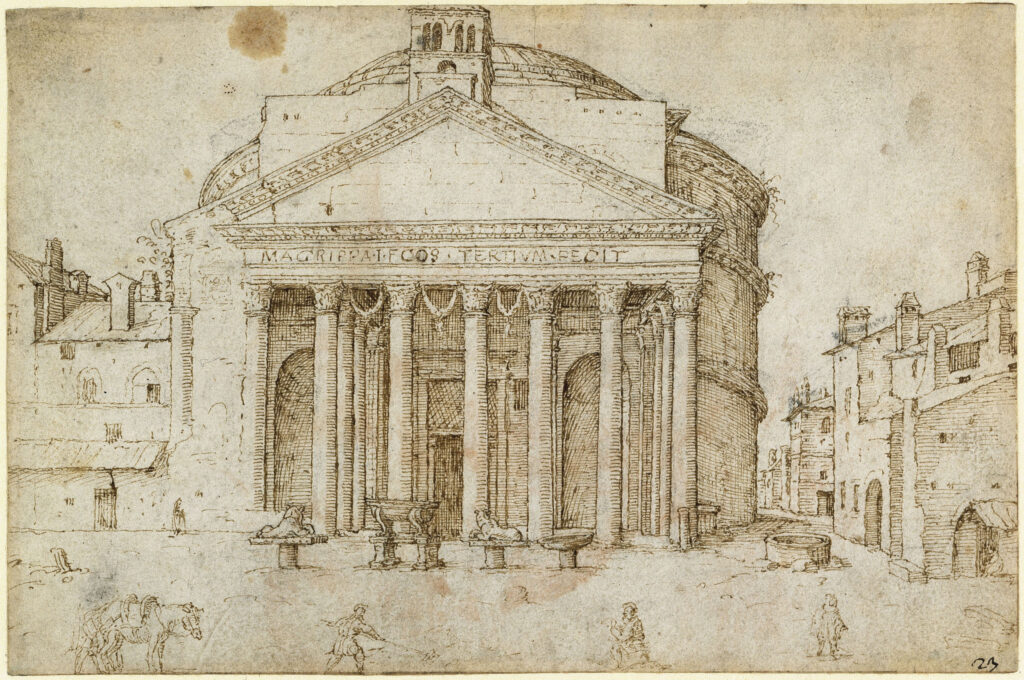

These primary sources show the Pantheon in the Piazza della Rotonda as it was restored in the seventeenth century and record changes that took place during the reign of Alexander VII, which will be discussed below. The Pantheon in this period showed modifications from the previous century, as Urban VIII had commissioned Carlo Maderno to add the twin towers to the façade, replacing the one campanile visible during the earlier medieval period (fig. 6).[3] Falda represents these twin towers, along with other restorations made under Urban VIII and Alexander VII.

Falda’s views provide visual detail for most of the piazza. One area, however, that raised questions was that blocked by the fountain in the Fontane view by Falda (fig. 3). This area is not depicted in another view by Falda nor is it depicted in Falda’s map. Falda’s Fontana nella Piazza della Rotonda shows the view of the fountain in the center of the piazza from the perspective of the Pantheon (fig. 3). While the view includes a lot of detail for the surrounding buildings, the fountain obscures the windows and ground floor doors of the buildings behind it. We needed to find sources for these details. Data on the changing Piazza della Rotonda indicates that this block of buildings has changed very little, although plans for great changes, discussed below, did take place. Modern photographs of this block of buildings on the Piazza della Rotonda reveal that a majority of the buildings have remained the same since the seventeenth century (fig. 7). The three-bay building at the west end displays largely the same façade as that shown in Falda’s print, whereas the building to the east in Falda’s print has lost two bays to a new, single-bay palazzo oriented toward the via del Pantheon (vicolo del Sole).[4] By comparing the four bays of the eastern building opposite the Pantheon in Falda’s Fontane print to the two western bays of the same eastern building in a modern photograph, we were able to reconstruct the general appearance of the four bays in 1676. The modern photograph (fig. 7) also provides additional detail on what the windows on the western building opposite the Pantheon would have looked like, including a door with a small balcony that is partially obscured by water in Falda’s print.

Multiple changes took place in the Piazza della Rotonda over the centuries. The level of the ground in the piazza itself changed multiple times. In the sixteenth century the piazza had risen high enough that a thirteen-step stair was required to walk down into the building.[5] Over the next century the piazza was lowered numerous times. During Falda’s time, the piazza was again lowered, as can be seen in a comparison of his prints of the piazza in Il nvovo teatro (fig. 4 and 5). In the print Piazza Della Rotonda Ampiata Da N.S. Papa Alesandro VII from vol. 1, published c. 1665, the ground level clearly covers the bases of the columns of the Pantheon. In the later print from vol. 2, print 3, Piazza della Rotonda Ampliata Spianata Con Le Strade Intorno Da N.S. PP. Alessandro VII, published c. 1667, the same column bases are now uncovered due to the lowering of the piazza level. This grading took place in 1666 under the order of Pope Alexander VII, as a part of his larger vision for the piazza.[6]

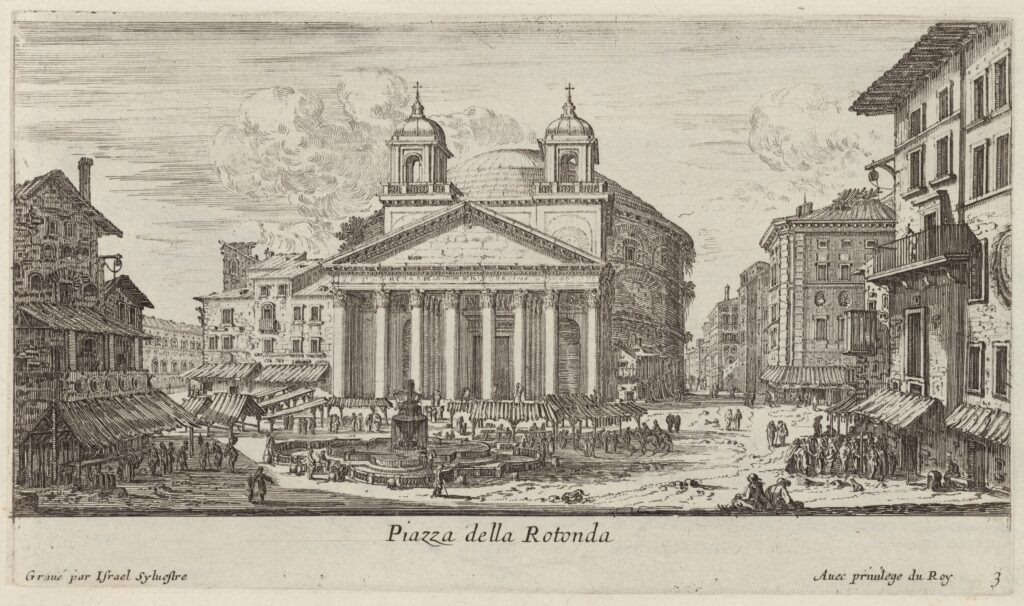

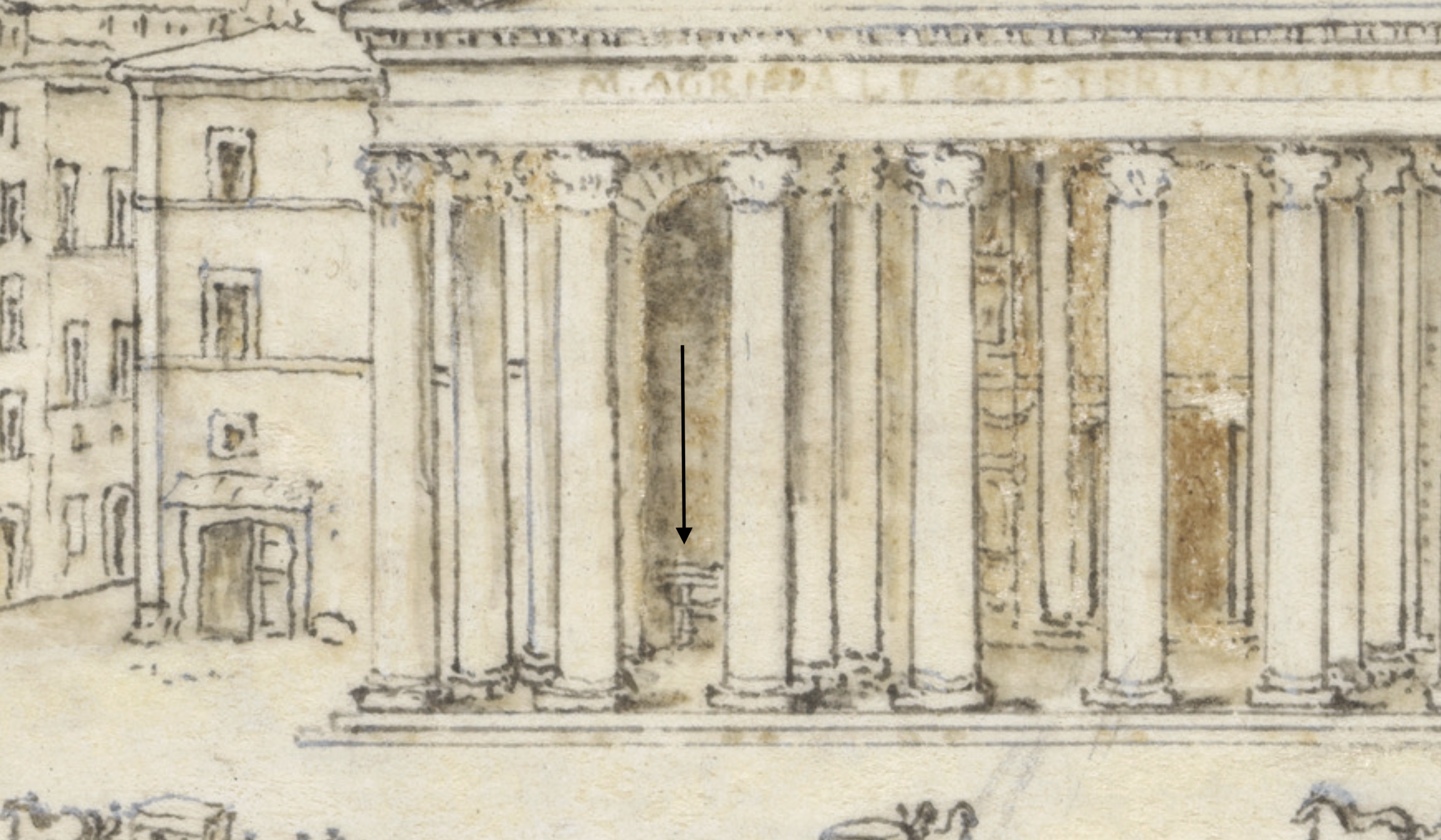

As a part of the same vision for the repair and restoration of the piazza, Alexander VII ordered that the damaged columns on the eastern side of the Pantheon porch be restored, using ancient column pieces taken from the ruins of the Baths of Nero (Thermae Neronis), also called the Baths of Alexander (Thermae Alexandrinae), which were built under Nero and renovated under Alexander Severus, located nearby S. Luigi dei Francesi. This work took place between 1661 and 1667.[7] Two related columns remain near San Eustachio. One can see the earlier state of the columns and a piece of the entablature, still absorbed into the attached buildings housing the canons and other shops, in a print by Martin van Heemskerck from 1532-1536 (fig. 6). Before the work of Alexander VII to restore the eastern two columns at back left, Urban VIII restored the first column on this side and the entablature above it.[8] An illustration by Domenico Castelli in the Vatican Library outlines the repaired sections of the entablature, along with exhibiting the then new twin bell towers above.[9] This state is visible in a print by Israel Silvestre (fig. 8), which shows the first column on the left, or eastern, side, but is vague with respect to the back two. Falda’s first view of the Piazza della Rotonda (fig. 4) matches the angle of Silvestre’s print and much of the detail, but Falda shows the houses of the canons and associated buildings regularized and cut back from the porch and all of the columns replaced. In his second view (fig. 5) he also depicts the piazza lowered and the porch clear.

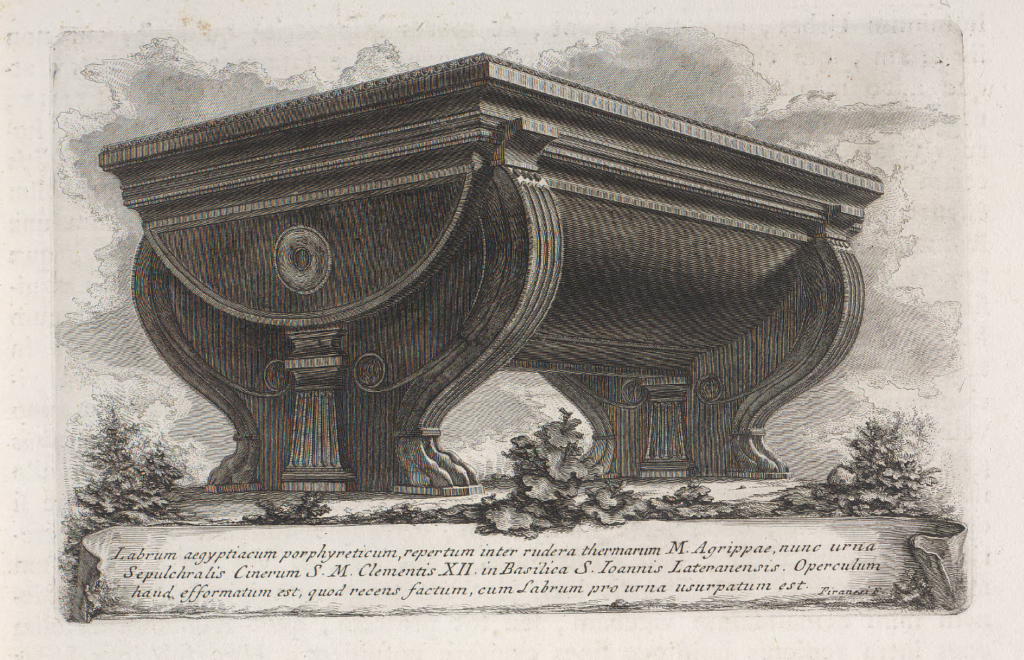

A discrepancy between Falda’s maps and his prints that had to be reconciled was the presence of a decorative basin in the center of piazza, just in front of the Pantheon porch. While Falda depicted it in both of his prints from the Nuovo Teatro, it was present in neither of his maps from 1667 or 1676.[10] The basin was originally from the Baths of Agrippa, just south of the Pantheon. The basin was discovered under Pope Eugene IV in 1443, who cleared the porch of the Pantheon of the huts that had been built into it as well as cleaned the Piazza della Rotunda of rubble from ancient buildings. Under Clement VII in 1523-1525, the basin was placed in front of the porch of the Pantheon.[11] Falda depicts the basin in this location in both of his Nuovo Teatro prints (figs. 4 and 5) and Silvestre depicts it in this location, as well (fig. 8). Falda does not, however, depict the basin in either his 1676 map (fig. 1) or his 1667 map, and neither does Nolli (fig. 2). The basin was later moved to St. John’s Lateran to be used for the burial of Clement XII (1740) in the Corsini Chapel where it remains today.[12] Giovanni Battista Piranesi depicted the basin in his Il Campo Marzio dell’Antico Roma, 1762, recording its Lateran location (fig. 9). Its absence from Falda’s map can be explained by an additional move during the period after it

was set up in the Piazza della Rotunda and before it was removed to the Lateran. Around 1662, the basin was moved to a position beneath the eastern end of the porch of the Pantheon where it can be seen in Lieven Cruyl’s depiction of the Pantheon (figs. 10 and 11).[13] At the time of Falda’s map in 1676, the basin would have been located beneath the porch of the Pantheon, and therefore not visible in the bird’s eye view.

-

Figure 10: L. Cruyl, View of the Pantheon, Rome, early 1670s. -

Figure 11: Detail with arrow for emphasis by author from L. Cruyl, View of the Pantheon, Rome, early 1670s.

Another question about the appearance of the Piazza della Rotonda during the time of Falda centered on the presence or absence of “casini” or market stalls. Falda shows them in “Piazza della Rotonda Ampliata Spianata Con Le Strade Intorno Da N.S. PP. Alessandro VII” (fig. 5), but not in his other prints or maps. The market stalls were a point of contention during the reign of Alexander VII, as he tried to clean up the Piazza della Rotonda. The disorganized state of these market stalls before Alexander VII’s interventions can be seen in a print by Israel Silvestre where they appear, randomly placed, between the fountain and the Pantheon, and are even attached to the sides of the Pantheon itself (fig. 8). Alexander VII issued a brief in 1662 referring to his work to “rescue the Pantheon from the squalor of the market,” which included moving the sellers and fishmongers from this piazza to the Piazza di Pietra.[14] Over the course of 1662 efforts continued to be made to keep the vendors in the Piazza di Pietra, despite protests from the vendors as well as the canons of the chapter who were missing out on rental income. In 1663 Alexander VII had to concede to the opposition, and the casini were restored in specific spaces in the Piazza della Rotonda.[15] In fact, as late as the Catasto Urbano – Pio Gregoriano of 1824, these market stalls appear and are described as Della Pescaria sulla Piazza della Rotonda being used as “casotti” under the proprietorship of the Capitolo di S. Maria ad Martyres.[16] The footprint of the market stalls following Alexander VII’s concession can be seen in a 1663 drawing produced by the Notai del tribunale delle acque e strade at the time when the stalls were being restored, as well as in a 1710 drawing produced by the Presendenza delle Strade that depicts the plan and section of the casini “in legno da ricostruire in muratura.”[17] The post-Alexander VII footprint of the market stalls can also be found in the later Nolli map. A view of these buildings from the perspective of the Pantheon porch can be found in the Renard print of the Piazza della Rotonda dated to 1711.[18] Piranesi’s 1751 Veduta della Piazza della Rotonda actually depicts the Pantheon from a perspective just behind one of these buildings, showing them in great detail (fig. 12). We decided not to depict the casini in Envisioning Baroque Rome, as Falda does not depict them on his map (fig. 1), nor in his Fontana print (fig. 3) or his first Il nuovo teatro print (fig. 4), only showing them in his second Il nuovo teatro print (fig. 5). The absence of these market stalls in most of his depictions of the Piazza della Rotonda highlights the fact that Falda is presenting the square as Pope Alexander VII wanted it to be.

In the nineteenth century, great focus was placed on isolating the Pantheon from the surrounding buildings and exhibiting its Roman foundations, finally completing some of the goals of Alexander VII and others. The different stages of the process whereby the city purchased and removed the attached structures is well recorded (compare figs. 13 and 14). These images help to clarify the nature of the piazza in 1676. The last of the structures attached to the Pantheon was demolished by 1883 (fig. 14). Additionally, the Palazzo Crescenzi-Bonelli was partially demolished to provide a wider via della Rotonda by 1883, and by 1890 the gabled building jutting into the piazza on the east, visible in Falda’s print (fig. 4), was knocked down.[19]

-

Figure 13: Detail of the Piazza della Rotonda from Direzione Generale del Censo, Pianta topografica di Roma: aggiornata a tutto il corrente, 1866. -

Figure 14: Detail of the Piazza della Rotondo from Spinetti, A. Pianta topografica di Roma, 1883.

Also, in this period there was a plan to purchase and remove the block opposite the Pantheon completely in order to “place the Pantheon in a better light, in the center of a large square, which might afford on every side the right point of perspective, as it was the case in ancient times.[20]” A report from this period states that the “houses facing the piazza [della Rotonda] on the east side have already been bought and will soon be demolished; [and] the same fate awaits the block of houses between the Piazza della Rotonda and della Maddalena.”[21] While the plan to transform this space is recorded, it was never completed. The sequence of changes made to this piazza is evident in maps made over the 18th and 19th centuries. In the Pianta di Roma of Giambattista Nolli (fig. 2) the blocks follow the pattern also visible in Falda’s map (fig. 1), but by 1866 (fig. 13) the process of extricating the ancient Pantheon from the buildings affixed to it has begun and those along the Pantheon façade have been removed. Further, in the 1883 Pianta topografica di Roma by Antonio Spinetti (fig. 14) one can see that the houses “on the east side” of the Piazza della Rotonda have been partially cleared, and the roads around the Pantheon have been widened by the removal of portions of the surrounding blocks.[22] However, the block between the Piazza dell Rotonda and the Piazza della Maddalena remains even today.

Piazza della Minerva

-

Figure 15: G.B. Falda, Piazza di Santa Maria della Minerva, 1665-67. -

Figure 16: G.B. Falda, Altra Veduta della Piazza di S. Maria della Minerva, 1665-67.

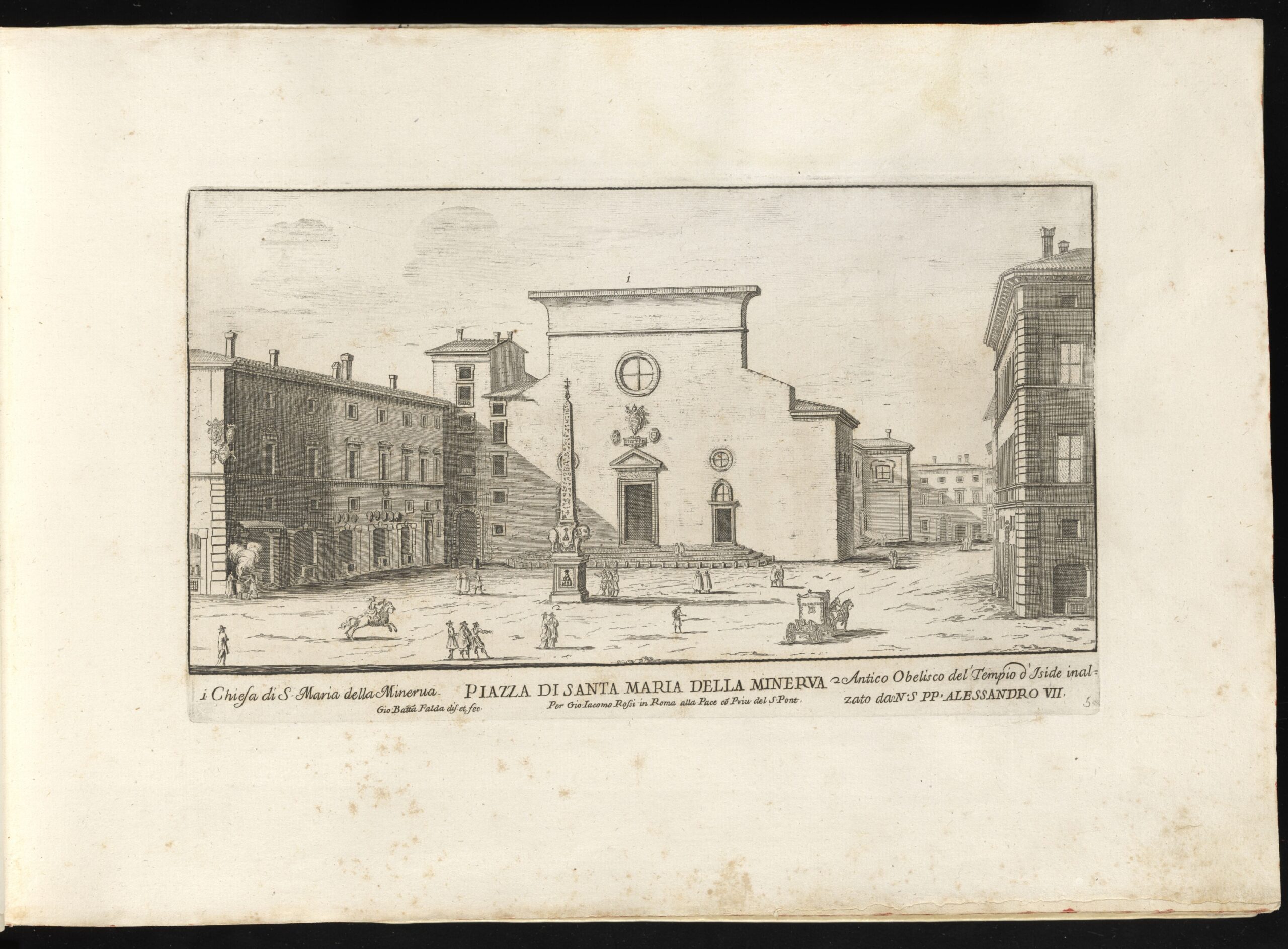

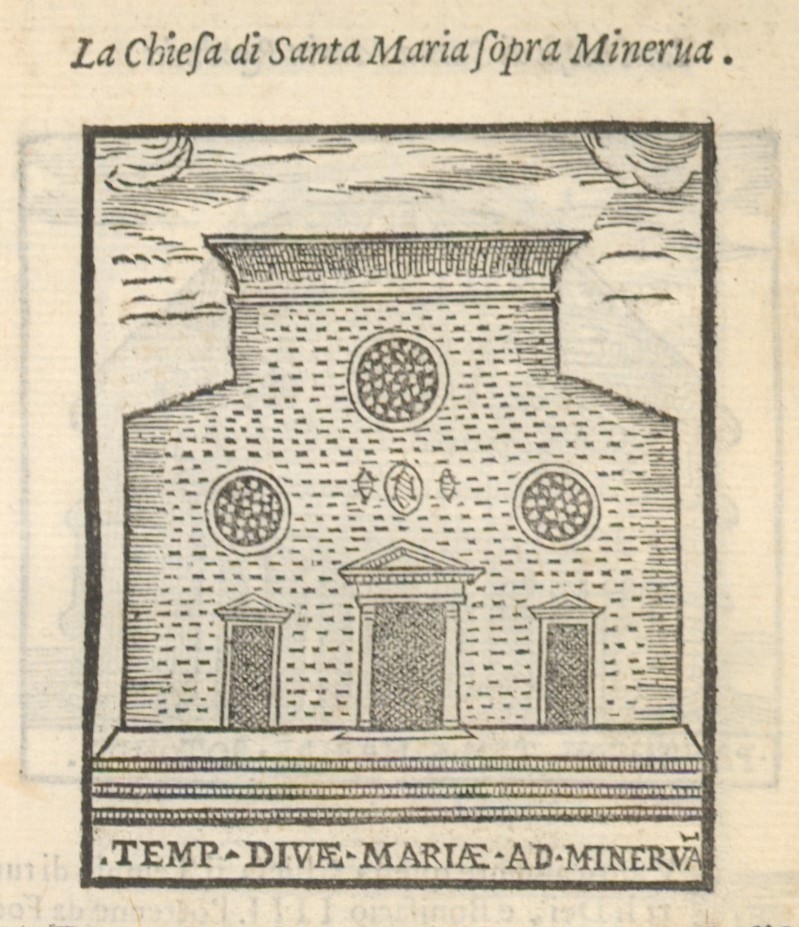

The Piazza della Minerva is located southeast of the Pantheon. The piazza was depicted by Giovanni Battista Falda less for the church and its unfinished façade than for the new work of sculpture and restored obelisk placed in front of the church. Falda illustrates two views of this piazza in Il nvovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna, vol. 2, print 5, Piazza di Santa Maria della Minerva (fig. 15), and print 6, Altra Veduta della Piazza di S. Maria della Minerva (fig. 16). For comparison, an earlier view of this church can be found in Girolamo Francino’s guide to Rome from 1588 (fig. 17). A later view of the church by Alessandro Moschetti shows changes to the façade that took place after Falda’s day, and provided us with a comparison for other buildings on the piazza (fig. 18).

-

Figure 17: Franzini, G., and A. Palladio, Temp Divae Mariae ad Minerva, 1588. -

Figure 18: Moschetti, A. Piazza della Minerva, 1846.

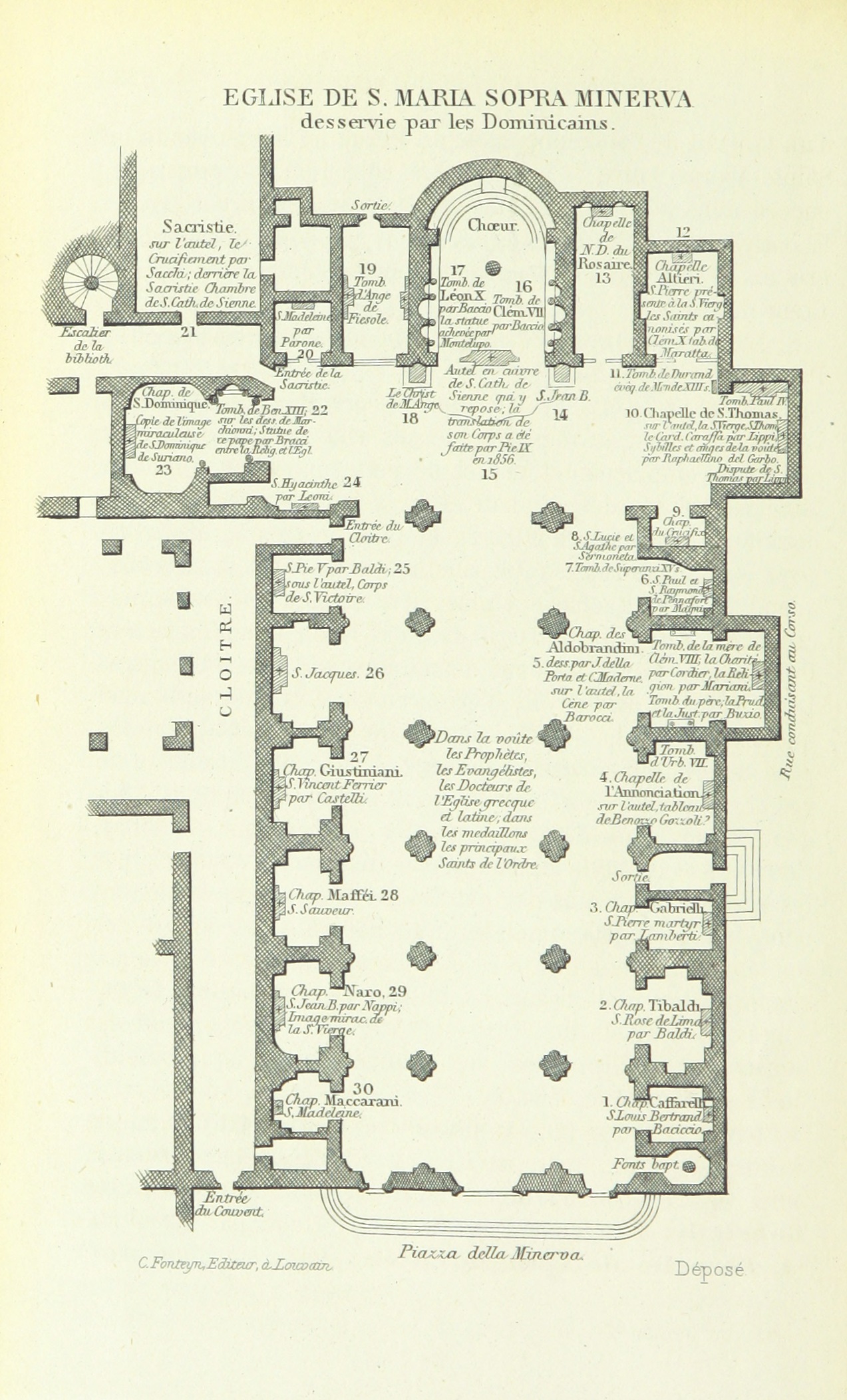

For detail on the plan of the church and the surrounding block we referenced two sources. First, a plan of the church from 1866 (fig. 19) shows the same plan as that found on Nolli’s map (fig. 2), providing more detail and a precise scale. Second, a plan of the block containing Santa Maria sopra Minerva from the Archivio di Stato, illustrating the portions of that block that in 1812 had been the Convento della Minerva and which were now being transferred to the Amministrazione del Debito Publico to be added to the Caserma Militare, provided helpful detail on the surrounding buildings.[23]

Within the adjacent Convento della Minerva, the meetings of the Congregazione del Santo Uffizio took place, including the inquisition and recantation of Galileo Galilei in 1633. The latter event was celebrated in Santa Maria sopra Minerva and was seen at the time as a victory for the church, and convent, supported by Pope Urban VIII. In 1634, the Dutch artist Herman van Swanevelt was held here for breaking a fast. One of two lunettes that he created before he was released remains in the church.[24] In 1665, an obelisk was uncovered in the Convento dei Domenicani dating from the 6th century BCE. It was brought to Rome in the 1st century CE for the Temple of Isis. Pope Alexander VII commissioned the elephant statue that now supports it in the Piazza della Minerva from Bernini’s workshop.[25] The elephant sculpture was carved by Ercole Ferrata, though drawings of the overall design by Bernini exist from as early as the 1630’s. The sculpture of the elephant and obelisk was dedicated by Alexander VII in 1667.[26] This was Alexander VII’s last commission from Bernini’s workshop, and a key point for Falda to highlight in his prints. The elephant and obelisk appear in Falda’s first full map of Rome that he created on two plates, the Recentis Romae ichnographia et hypsographia sive planta et facies ad magnificentiam qva svb Alexandro VII P.M. vrbs ipsa directa excvlta et decorata est (fig. 20), and scholars use this sculpture to date the map to 1667.[27]

[1] Marder 1991, 282. Marder discusses the position of the piazza as influencing its importance.

[2] The terminus ante quem for this image is 1678, the year of Falda’s death, though the publication was later.

[3] Marder 1991, 275.

[4] A print by Benedykt Renard, who signed his works under the name Benedetto Renard Polacco, dated 1711, shows this eastern building still intact with four bays, as in Falda, though Renard shows the building divided as two two-bay units. (Renard and Barigioni 1711, https://www.calcografica.it/stampe/inventario.php?id=S-FC116309, https://exhibits.stanford.edu/lanciani/catalog/rd798gw0405). A Richiesta di licenza edilizia for the expansion of the roof to a terrace of the easternmost building from the Archivio del Comune pontificio dating to between June and August of 1868, indicates a terminus ante quem, before which the two eastern bays had been sold (Descriptio Romae, Castasto Urbano – Pio Gregoriano, “Particella: 62 | Rione: S. Eustachio,” http://www.dipsuwebgis.uniroma3.it/gamma_1/index.phtml).

[5] Marder 1991, 274. This staircase is visible in a drawing by Martin van Heemskerck (https://nat.museum-digital.de/object/587152).

[6] Marder 1991, 283.

[7] Marder 1991, 283-284. Marder notes that a chirograph from November 4, 1662 grants the right to move the columns, though it also states that some of the pieces had already been moved at this time.

[8] Pietrangeli 1977, 24-26.

[9] Rice 2008, 351-352. See B.A.V. Manuscript – Barb.lat.4409, f. 62r. https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Barb.lat.4409

[10] Falda’s print from Le Fontane leaves it out of view.

[11] Lombardo, Alberto. 2003 Vedute del Pantheon attraverso i secoli, 14.

[12] You can see a photograph of the tomb in the Alinari Archives. Archivi Alinari, Firenze – Collezione: Archivi Alinari-archivio Anderson, Firenze – AVVERTENZA: Autorizzazione obbligatoria per utilizzi non editoriali: rivolgersi ad Archivi Alinari – Dimensione (pixel): 1944 X 2532 – Dimensione (cm a 300 dpi): 16 X 21 – Dimensione (MB): 3.33 – Color space: RGB – URL: https://www.alinari.it/img-thumb/640/ADA/ADA-F-020941-0000.jpg

[13] Pietrangeli 1977, 30, 44.

[14] Marder 1991, 280, citing Krautheimer 1985, 184, citing BAV, Pantheon II.1, no. 22, 117-119 (20 June 1662).

[15] Marder 1991, 281-282.

[16] Descriptio Romae, Particella 66, 67 in Rione S. Eustachio. http://www.dipsuwebgis.uniroma3.it/gamma_1/index.phtml (accessed 5/16/2023).

[17] Archivio dello Stato di Roma Segnatura: 81 – 285 / 1 and Archivio dello Stato di Roma Segnatura: 81 – 284 / 1.

[18] Renard and Barigioni 1711, “Prospetto della Piazza della Rotonda e Fontana Nvovamente.” https://www.calcografica.it/stampe/inventario.php?id=S-FC116309, https://exhibits.stanford.edu/lanciani/catalog/rd798gw0405 (Accessed 7/27/2025).

[19] Ceen 2009, 137.

[20] Buckingham et al. 1882, 289.

[21] Buckingham et al. 1882, 289.

[22] Ceen 2009, 137-138.

[23] Archivio di Stato di Roma, Collezione disegni e mappe – Collezione I, Segnatura: 86 – 523 / 1. Pietro Holl, architetto, 1812.

[24] The second lunette is lost. Russell 2001, 132-137; Pietrangeli 1977, 74.

[25] Pietrangeli 1977, 76-78; Heckscher 1947, 155-157.

[26] Pietrangeli 1977, 76-78; Heckscher 1947, 155-157.

[27] McPhee 2013, 31.

Figures:

- Figure 1: “Detail of the Piazza della Rotonda” from Giovanni Battista Falda. 1676. Nuova pianta et alzata della citta’ di Roma con tutte le strade, piazza et edificii de tempi, palazzi, giardini et altre fabbriche antiche e moderne come si trovano al presente nel pontificato do N.S. Papa Innocentio XI con le loro dichiarationi nomi et indice copiosissimo. Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Object number: RP-P-OB-207.658 (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by the Rijksmuseum, http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.587478).

- Figure 2: “Detail of the Piazza della Rotonda” from Giambattista Nolli. 1748. Nuova Pianta di Roma. Roma: s.n. Collection Archive.org (https://archive.org/details/gri_33125008447415/page/n30) (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Archive.org and scanned by Getty Research Institute).

- Figure 3: Falda, Giovanni Battista. “Fontana nella Piazza della Rotonda.” in Le fontane di Roma nelle piazze e luoghi publici della città, con li loro prospetti, come sono al presente. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Emory University Readux).

- Figure 4: Falda, Giovanni Battista. 1665. “Piazza Della Rotonda Ampiata Da N.S. Papa Alesandro VII” in Il nvovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna, vol. 1, print 31. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Emory University Readux https://readux.io/volume/nuovoteatro5vol/page/nuovoteatro5vol_00000065.tif).

- Figure 5: Falda, Giovanni Battista. 1669. “Piazza della Rotonda Ampliata Spianata Con Le Strade Intorno Da N.S. PP. Alessandro VII” in Il nvovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna, vol. 2, print 3. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Emory University Readux https://readux.io/volume/nuovoteatro5vol/page/nuovoteatro5vol_00000079.tif).

- Figure 6: van Heemskerck, Maarten. 1532-1536. “Ansicht des Pantheons von vorn,” from Römisches Skizzenbuch I. Collection of the Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided CC BY-NC-SA by the Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin https://nat.museum-digital.de/singleimage?resourcenr=803835).

- Figure 7: Grandmont, Jean-Pol. 2011. “La fontaine (1578) de Giacomo Della Porta couronnée de l’obélisque dit de Macuteo en 1711 sur la Piazza della Rotonda, Rome (Italie).” (artwork CC-BY 4.0, photograph provided Jean-Pol Grandmont through Wikipedia CC-BY https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Fontana_di_piazza_della_Rotonda_(Rome)#/media/File:0_Piazza_della_Rotonda_-_Fontaine_Gacomo_della_Porta_%C3%A0_Rome_(1).JPG).

- Figure 8: Silvestre, Israel. 1640-1660. “Piazza della Rotonda.” Collection of the National Gallery of Art, Accession Number 1981.69.12.213 (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided public domain by the National Gallery of Art https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.164623.html).

- Figure 9: Piranesi, Giovanni Battista. 1762. “Piranesi’s dedication page honoring Robert Adam, the British architect who had become his friend” in Campus Martius Antiquae Urbis / Il Campo Marzio dell’Antica Roma. Collection of the St. Louis Public Library, Call Number Steedman 760 A3W Vol[11] (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided no copyright by the St. Louis Public Library Digital Collections https://cdm17210.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/steedman/id/192/rec/2).

- Figure 10: Cruyl, Lieven. Early 1670s. “View of the Pantheon, Rome.” Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Accession Number: 1974.1.578 (artwork in the public domain, photograph provdied public domain by the Metropolitan Museum of Art https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/459349).

- Figure 11: “Detail of the basin” from Lieven Cruyl. Early 1670s. “View of the Pantheon, Rome.” Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Accession Number: 1974.1.578 (artwork in the public domain, photograph provdied public domain by the Metropolitan Museum of Art https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/459349

- Figure 12: Piranesi, Giovanni Battista. 1751. “Veduta della Piazza della Rotonda,” from Vedute di Roma. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Accession Number: 37.45.3(52) (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided public domain by the Metropolitan Museum of Art https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/363427).

- Figure 13: “Detail of the Piazza della Rotonda” from Direzione Generale del Censo. 1866. Pianta topografica di Roma: aggiornata a tutto il corrente. Collection of the Bibliotheca Hertziana. (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided CC-BY-NC by the Bibliotheca Hertziana https://dlib.biblhertz.it/Dg155-4660)

- Figure 14: “Detail of the Piazza della Rotonda” from Antonio Spinetti. 1883 or later. Pianta topografica di Roma […]. Collection of The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided the Getty Research Institute Open Content Program CC-0 https://primo.getty.edu/primo-explore/fulldisplay?vid=GRI-OCP&docid=GETTY_OCPFL2115896&context=L&tab=all_gri&lang=en_US).

- Figure 15: Falda, Giovanni Battista. 1669. “Piazza di Santa Maria della Minerva” in Il nvovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna, vol. 2, print 5. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Emory University Readux https://readux.io/volume/nuovoteatro5vol/page/nuovoteatro5vol_00000083.tif).

- Figure 16: Falda, Giovanni Battista. 1669. “Altra Veduta della Piazza di S. Maria della Minerva” in Il nvovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, in prospettiva di Roma moderna, vol. 2, print 6. Collection of Emory University Libraries (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Emory University Readux https://readux.io/volume/nuovoteatro5vol/page/nuovoteatro5vol_00000085.tif).

- Figure 17: Francini, Girolamo, and Andrea Palladio. 1588. “Temp Divae Mariae ad Minerva.” in Le cose maravigliose dell’alma città di Roma, dove si veggono il movimento delle guglie, & gli acquedutti per condurre l’Acqua Felice, le ample, et commode strade, fatte a beneficio publico dal santissimo Sisto V p.o.m…. In Venetia: per Girolamo Francino. Collection of the ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Rar 6833: 1 (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by ETH-Bibliothek Zürich public domain https://doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-9315).

- Figure 18: Moschetti, Alessandro. 1846. “Piazza della Minerva” from Raccolta Delle Principali Vedute Di Roma Antica E Moderna. Collection of Heidelberg University Library. (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided public domain by Heidelberg University Library https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/moschetti1846/0012/image,info,thumbs).

- Figure 19: De Bleser, Édouard Philippe Jacques. 1866. Rome et ses monuments: guide du voyageur catholique dans la capitale du monde chrétien. Louvain: C.-J. Fonteyn. Collection of the British Library, British Library HMNTS 10136.i.22. (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by the British Library through wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:348_of_%27Rome_et_ses_monuments._Guide_du_voyageur_catholique_dans_la_capitale_du_monde_chr%C3%A9tien_…_Avec_cinquante-et-un_plans_annot%C3%A9s%27_(11072305715).jpg).

- Figure 20: Falda, Giovanni Battista. 1667. Recentis Romae ichnographia et hypsographia sive planta et facies ad magnificentiam qva svb Alexandro VII P.M. vrbs ipsa directa excvlta et decorata est. Collection of the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, FOLIO 2012 43. (artwork in the public domain, photograph provided by Emory University Readux https://readux.io/volume/thgrb/page/all).

Bibliography

- Buckingham, J.S., J. Sterling, F.D. Maurice, H. Stebbing, C.W. Dilke, T.K. Hervey, W.H. Dixon, N. Maccoll, V.H. Rendall, and J.M. Murry. 1882. The Athenaeum: A Journal of Literature, Science, the Fine Arts, Music, and the Drama: J. Francis.

- Ceen, Allan. 2009. The Urban Setting of the Pantheon. In The Pantheon in Rome: Contributions to the Conference, Bern, November 9-12, 2006, edited by Gerd Grasshoff, Michael Heinzelmann and Markus Wäfler. Bern.

- Heckscher, William S. 1947. “Bernini’s Elephant and Obelisk.” The Art Bulletin 29 (3):155-82.

- Krautheimer, Richard. 1985. The Rome of Alexander VII, 1655-1667. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Marder, Tod A. 1991. “Alexander VII, Bernini, and the Urban Setting of the Pantheon in the Seventeenth Century.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 50 (3):273-92.

- McPhee, S. 2013. Teatro. In Antichità, Teatro, Magnificenza: Renaissance & Baroque Images of Rome: Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University.

- Pietrangeli, Carlo. 1977. Rione IX – Pigna Parte 2, Guide Rionali di Roma. Roma: Fratelli Palombi Editori.

- Renard, Benedykt, and Filippo Barigioni. 1711, (Accessed July 28). “Prospetto della Piazza della Rotonda e Fontana Nvovamente… https://www.calcografica.it/stampe/inventario.php?id=S-FC116309 and https://exhibits.stanford.edu/lanciani/catalog/rd798gw0405.

- Rice, Louise. 2008. Bernini and the Pantheon Bronze. In Sankt Peter in Rom, 1506-2006. Beiträge der internationalen Tagung vom 22. – 25. Februar 2006 in Bonn, edited by G. Satzinger and S. Schütze. Munich: Hirmer.

- Russell, Susan. 2001. “A Drawing by Herman van Swanevelt for a Lost Fresco in S. Maria sopra Minerva, Rome.” The Burlington Magazine 143 (1176):132-7.

Leave a Reply